This entry is part of Park Views, a weekly Asheville Parks & Recreation series that explores the history of the city’s public parks and community centers – and the mountain spirit that helped make them the unique spaces they are today. Read more from the series and follow APR on Facebook and Instagram for additional photos, upcoming events, and opportunities.

O Stephens-Lee, dear Stephens-Lee, our hearts are filled with love for thee; A champion brave, thy youth to save – thy children honor thee. Home of truth we do believe, noble deeds thou wilt achieve; in sun or rain we shall remain faithful to thee, dear Stephens-Lee.

O Stephens-Lee, dear Stephens-Lee, our hearts are filled with pride for thee; a warrior bold – the right uphold – alma mater, dear, when upon thoughts will turn to thee; from day to day, crimson and gray, praise we Stephens-Lee.

Though Stephens-Lee High School’s final graduation took place in 1965, the words of its alma mater – written by faculty member and glee club director Ollie M. Reynolds – are still remembered by alumni today. Known as “The Castle on the Hill,” the school was well known across the southeast for its excellence in academics, athletics, and the arts. Today, it continues its legacy as a community center.

Dr. Edward Stephens and Hester Ford Lee

Stephens-Lee opened on March 7, 1923, but was actually the second school on the site. Four years before the U.S. Supreme Court’s “separate but equal” decision in Plessy v. Ferguson, Catholic Hill School opened in 1892. Isaac Dickson, the first Black member of the local school board, earlier helped establish Beaumont Street and Mountain Street schools for the area’s Black students. He recruited Dr. Edward S. Stephens, who taught at both schools, to serve as principal and fifth grade teacher at Catholic Hill. Stephens became Asheville’s first Black principal.

Stephens-Lee opened on March 7, 1923, but was actually the second school on the site. Four years before the U.S. Supreme Court’s “separate but equal” decision in Plessy v. Ferguson, Catholic Hill School opened in 1892. Isaac Dickson, the first Black member of the local school board, earlier helped establish Beaumont Street and Mountain Street schools for the area’s Black students. He recruited Dr. Edward S. Stephens, who taught at both schools, to serve as principal and fifth grade teacher at Catholic Hill. Stephens became Asheville’s first Black principal.

Stephens was born in the British West Indies and spent his earliest years as a butler in the home of Guyana’s British governor. Following the death of his father, he was adopted by the governor’s family. When the governor returned to England, Stephens studied at top European academic institutions, served as a missionary in Africa, mastered seven languages, and spent time in Switzerland, Germany, and France before arriving in Asheville in 1890. Soon after, he hosted a public meeting with Dickson to organize the Young Men’s Institute and convinced George Vanderbilt to support the project with a $10,000 loan. After clashes with the school board over inadequate funding, he moved with his wife Izie to Topeka, Kansas by 1894 or 1895.

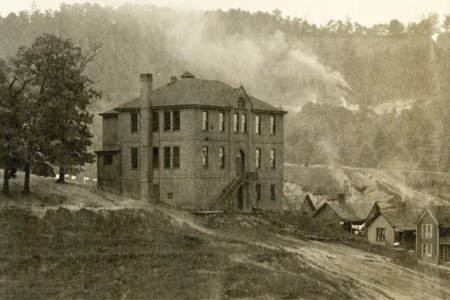

In 1909, Walter Lee became principal of Catholic Hill School, a position he also held at Stephens-Lee until his death in 1934. Seven students were killed and several others injured when the school’s furnace malfunctioned and fire consumed the building in 1917.

Black students spent the next six years attending classes in cramped quarters at the former Circle Terrace Sanitorium; still, there was enough demand that a third year of high school was added in 1921. That same year, Asheville voters approved a bond referendum to finance a new high school for Black students and a new elementary school for white students that became Claxton Elementary School. The following year, the school board dedicated the future site of Stephens-Lee High School, naming the new school for Stephens and Hester Ford Lee, Walter Lee’s wife.

Black students spent the next six years attending classes in cramped quarters at the former Circle Terrace Sanitorium; still, there was enough demand that a third year of high school was added in 1921. That same year, Asheville voters approved a bond referendum to finance a new high school for Black students and a new elementary school for white students that became Claxton Elementary School. The following year, the school board dedicated the future site of Stephens-Lee High School, naming the new school for Stephens and Hester Ford Lee, Walter Lee’s wife.

A beloved educator at Catholic Hill, she originally came to Asheville as one of the five teachers who opened Beaumont Street School. After briefly moving to Tennessee, she returned with her husband in 1905. She again taught in Asheville and was principal teacher of her school at a time when very few women of any race were given principalships. Lee died suddenly in 1922.

Castle on the Hill

From the moment it opened in 1923, Stephens-Lee’s Academic Gothic style building became a center for Black culture and education throughout the North Carolina mountains. When one of the only other high schools for Black students in the region burned down, students made a daily four and a half hour trip in an unheated bus from Yancey County to attend the school. With the only remaining Black high school in the area located in Hendersonville, Stephens-Lee attracted students from throughout western North Carolina.

From the moment it opened in 1923, Stephens-Lee’s Academic Gothic style building became a center for Black culture and education throughout the North Carolina mountains. When one of the only other high schools for Black students in the region burned down, students made a daily four and a half hour trip in an unheated bus from Yancey County to attend the school. With the only remaining Black high school in the area located in Hendersonville, Stephens-Lee attracted students from throughout western North Carolina.

Educated at Livingstone College and Columbia University, Principal Lee was inspired by Booker T. Washington’s vision to build a curriculum around dignity, self determination, service to community, independence, and Shakespeare. According to Stephens-Lee Alumni Association, that meant courses in carpentry, radio repair, welding, home economics, and cosmetology alongside those in English literature, classical music, and drama. In 1953, a remarkable half of its teachers held master’s degrees.

Throughout the school year, concerts, art exhibits, plays, modern dance recitals, and chorus performances were presented to capacity crowds. Thriving on its connection to the community, the school’s trade classes even built houses in the surrounding neighborhood, some of which are still occupied today. Paul Dusenberry organized the school’s marching band in 1938. History teacher Madison “Doc” Lennon took over its direction in 1941 and the Stephens-Lee marching band thrilled locals with jazzy music, high-stepping drum majors, and talented majorettes for the next quarter century.

Throughout the school year, concerts, art exhibits, plays, modern dance recitals, and chorus performances were presented to capacity crowds. Thriving on its connection to the community, the school’s trade classes even built houses in the surrounding neighborhood, some of which are still occupied today. Paul Dusenberry organized the school’s marching band in 1938. History teacher Madison “Doc” Lennon took over its direction in 1941 and the Stephens-Lee marching band thrilled locals with jazzy music, high-stepping drum majors, and talented majorettes for the next quarter century.

The school also produced a number of prominent scholars with graduates excelling in their fields, becoming community leaders, teachers, entrepreneurs, lawyers, civil servants, entertainers, ministers, and athletes, among other occupations.

Stephens-Lee Bears and Bearettes

In 1941, an additional wing (the present-day community center) opened with a gymnasium upstairs and classrooms downstairs for vocational courses such as carpentry, masonry, and home economics. Constructed by WPA reusing many materials from the recently-razed Orange Street School, it was the only gym in any of Asheville’s schools for Black students at the time.

In 1941, an additional wing (the present-day community center) opened with a gymnasium upstairs and classrooms downstairs for vocational courses such as carpentry, masonry, and home economics. Constructed by WPA reusing many materials from the recently-razed Orange Street School, it was the only gym in any of Asheville’s schools for Black students at the time.

While competitive athletics had not been a focus of a Stephens-Lee education in its earliest years, sporting events drew spectators on the same level as its artistic performances. Coaches such as Oliver W. McCorkle and Clarence Moore always emphasized community programs and sports as recreation to enhance students’ spirits and intellectual experiences, rather than competition to elevate the elite few.

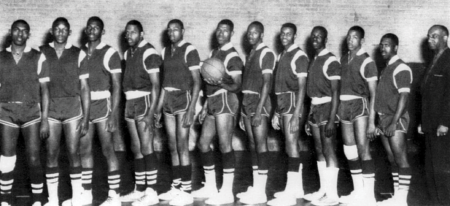

The football team won the national championship title in 1942. The Bears (men’s teams) and Bearettes (women’s teams) won multiple state titles and trophies in football, basketball, track, and tennis. Some athletes progressed to college and professional careers. Many student athletes’ experiences are recorded in The Greatest Sports Heroes of the Stephens-Lee Bears by Johnny Bailey and Bennie Lake.

Change is Gonna Come

Following the U.S. Supreme Court’s decision on Brown v. Board of Education in 1954 and subsequent rulings, Asheville’s public parks, community centers, pools, and golf course were no longer officially associated with individual races. However, the school system would not begin full-scale integration until a decade later.

The 1949 state school survey by North Carolina Department of Public Instruction found Stephens-Lee’s site “limiting,” hampering any plans to enlarge or modernize the campus. Student civil rights organizers formed Asheville Student Committee on Racial Equality (ASCORE) in the early 1960s to bring attention to the need for additional classrooms and address inequities between the city’s segregated schools, movie theaters, restaurants, job opportunities, public libraries, and institutions. ASCORE’s actions influenced the construction of a new high school for Black students on South French Broad Avenue.

The school board initially planned to continue to use Stephens-Lee as a middle school. Instead, 1965 was the last year a class graduated from Stephens-Lee High School and all remaining students moved to the new school. The French Broad Avenue school would later become Asheville Middle School and Lee H. Edwards High School would be renamed Asheville High School in 1969 following integration. After years of lower financial support than schools for white students, schools formerly for the Black community closed as the city’s schools consolidated.

The school board initially planned to continue to use Stephens-Lee as a middle school. Instead, 1965 was the last year a class graduated from Stephens-Lee High School and all remaining students moved to the new school. The French Broad Avenue school would later become Asheville Middle School and Lee H. Edwards High School would be renamed Asheville High School in 1969 following integration. After years of lower financial support than schools for white students, schools formerly for the Black community closed as the city’s schools consolidated.

Over the next decade, Stephens-Lee’s campus housed various nonprofit organizations. APR obtained use of the gym from the school board in 1966 for sports and recreation programs, moving equipment and supplies from Asheland Avenue and Valley Street community centers to the new address. From that point until the late 1970s, the site hosted night classes and programs for kids, teens, and older adults under the name Hill Top Community Center.

In 1975, City of Asheville purchased the property from Asheville City Schools for $10 with plans to develop a park and new community center. The original ornate building known as “The Castle on the Hill” was demolished less than a month later, but the gym wing was saved due to the work of Stephens-Lee alumni and Asheville Parks & Recreation (APR).

Center of Community

The building became a dedicated community center and employed a full-time director, but much of its original character remained intact. At the same time, the connection enjoyed by Stephens-Lee to former students’ neighborhoods was severed by urban renewal projects. Through the 1980s, many of the community center’s programs and activities were dependent on federal and state grants, leaving it without a clear identity among APR’s other recreation and community centers.

The building became a dedicated community center and employed a full-time director, but much of its original character remained intact. At the same time, the connection enjoyed by Stephens-Lee to former students’ neighborhoods was severed by urban renewal projects. Through the 1980s, many of the community center’s programs and activities were dependent on federal and state grants, leaving it without a clear identity among APR’s other recreation and community centers.

The name was changed to Stephens-Lee Recreation Center to connect the building to its rich history. It hosted thousands of community members each month in classes ranging from ceramics to rock climbing, but did not meet city codes for the afterschool and daycare programs requested by its neighbors.

In 1991, a reunion for all of Stephens-Lee’s alumni was held at the center. Expected to attract 100 people, nearly 800 showed up – some from as far as Hawaii. While sharing memories and talking about friends who passed away, the importance of preserving the school’s legacy took on greater urgency. Stephens-Lee Alumni Association became a nonprofit organization with a mission to keep alive the school’s principles by hosting reunions and granting scholarships. One scholarship recipient, Terry Bellamy, became the first Black mayor of Asheville.

Restoring a Landmark

Through the work of alumni, Stephens-Lee Community Center was designated a local historic landmark in 1996. Over the next two years, the building’s first major renovation added a new plaza and entry inspired by the original school, modernized former classrooms, and increased accessibility. For historic preservation of the building, Stephens-Lee Alumni Association received the Griffin Award from Preservation Society of Asheville & Buncombe County.

Through the work of alumni, Stephens-Lee Community Center was designated a local historic landmark in 1996. Over the next two years, the building’s first major renovation added a new plaza and entry inspired by the original school, modernized former classrooms, and increased accessibility. For historic preservation of the building, Stephens-Lee Alumni Association received the Griffin Award from Preservation Society of Asheville & Buncombe County.

APR established a project charter with the alumni association in 2017 to create designated space in the center to serve as a museum. The hallway leading to Stephens-Lee Alumni Room has personal photos, installations sharing the history of the school, crimson carpet, and an archway celebrating the original school building’s entrance. Though teachers forbid them from scratching their names on the gym’s pine wall paneling, many took a chance to leave a lasting mark on the building while attending Stephens-Lee. The paneling has been preserved and bears testament to the thousands of students who passed through the halls of “The Castle on the Hill,” inspiring today’s young people as they enter the gym.

Community members still pass through the doors of Stephens-Lee Community Center each week to connect over educational, cultural, and athletic experiences. Two playgrounds, a basketball court, and George Washington Carver Edible Garden can be found on the community center’s grounds. While it continues to serve a functional role in Asheville’s present, its first hundred years serve as an inspiration and symbol to everything that has been accomplished by the students who became leaders within its walls.

Community members still pass through the doors of Stephens-Lee Community Center each week to connect over educational, cultural, and athletic experiences. Two playgrounds, a basketball court, and George Washington Carver Edible Garden can be found on the community center’s grounds. While it continues to serve a functional role in Asheville’s present, its first hundred years serve as an inspiration and symbol to everything that has been accomplished by the students who became leaders within its walls.

For more on Stephens-Lee and Black roots in Asheville, read the Asheville African American Heritage Resource Survey.

Do you have photos or stories to share about Stephens-Lee? Please send them to cbubenik@ashevillenc.gov so APR can be inspired by the past as we plan our future.

Photo and Image Credits

- The marching band always made a well-anticipated appearance during the annual holiday parade. According to the Stephens-Lee newsletter, the band was “one of the most longed-for activities at the school” and members “performed with a rhythm and energy that thrilled onlookers.” Courtesy of University of North Carolina Asheville Special Collections.

- Catholic Hill’s three-story brick building stood near the location of the current community center from 1892 until it was destroyed by fire in 1917. Killing seven students and injuring many others, it represents one of the greatest tragedies in Asheville school history. Courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

- Until Stephens-Lee High School opened its doors, Black students attended classes in the former Circle Terrace Sanatorium. It’s believed this photo captures a group of students in front of the sanatorium. Courtesy of Ruth Jackson Cannon and Shirley Cannon Singleton Collection, Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina

- Modern dance students performed several times each year as part of Stephens-Lee High School’s emphasis on the arts. Courtesy of University of North Carolina Asheville Special Collections.

- Madison “Doc” Lennon served as the band director at Stephens-Lee for 25 years after earning degrees at Wilberforce and Ohio State universities. Along with Paul Dusenbury, Doc took the marching band throughout the southeast and compiled an impressive list of honors and awards. He was inducted into the North Carolina Bandmasters Association Hall of Fame in 2002. According to Stephens-Lee Alumni Association, Doc taught band members to play “legitimate concert music” and did not approve of rhythm and blues, though some of his students went on to play many styles of music professionally. Courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

- Stephens-Lee’s 1962 men’s basketball team won the 4-A state championship. Bennie Lake and Willie Maples went on to play for the Harlem Globetrotters, while Henry Logan would join the Oakland Oaks. Courtesy of Stephens-Lee Alumni Association.

- The original Stephens-Lee High School building was designed by local architect Ronald Greene and featured an Academic Gothic style of architecture. The gym on the right is in line with the style of WPA buildings of the time period. A renovation of Stephens-Lee Community Center in the late 1990s enhanced the entrance with a style closer to that of the original academic building. Since that time, a marker in the courtyard and archway in the main hallway have also brought back some of the style of “The Castle on the Hill.” Courtesy of University of North Carolina Asheville Special Collections.

- After the final class graduated in 1965, alumni continued to keep in touch on a regular basis through reunions. Many reunions have been held in Stephens-Lee’s gym. This group portrait shows the Class of 1960 celebrating their 25th anniversary in 1985. Original print by Clifford Cotton II. Courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

- Alumni returned to Stephens-Lee during the 1997 groundbreaking for the building’s first major renovation. The alumni association raised $5,400 in seed money with a $250,000 state grant and $1.6 million from City of Asheville funding the remainder.

- Though the gym wing is all that remains of Stephens-Lee High School, it has meaning beyond the physical building. Stephens-Lee is reflected in the hearts, lives, and actions of those involved with it through the years, both as an educational institution and community center. A plaque dedicated in 2001 reads: “Before you is the original cornerstone from the beloved ‘Castle on the Hill.’ Stephens-Lee High School, erected in 1922, served Buncombe and surrounding counties as the only public high school dedicated to the education of African American students. The school was closed in 1965 following the Supreme Court’s ruling that segregated schools were unconstitutional; schools were consolidated. The main portion of Stephens-Lee was demolished. Thanks to the combined efforts of the Stephens-Lee Alumni Association and the City of Asheville, this building which housed the gymnasium, home economics, and trade school was kept intact.”