This entry is part of Park Views, a weekly Asheville Parks & Recreation series that explores the history of the city’s public parks and community centers – and the mountain spirit that helped make them the unique spaces they are today. Read more from the series and follow APR on Facebook and Instagram for additional photos, upcoming events, and opportunities.

Richmond Hill Park wasn’t always the verdant escape Asheville residents know today. Following years of debate, the park’s transformation began with community members advocating for natural spaces close to home. Through dedication and sweat equity – and a vote of confidence in the form of bond funding – the expansive park is one of the city’s most treasured spaces.

Richmond Pearson: Lawyer, Diplomat, Developer

A lawyer by trade, Richmond Pearson donned many hats throughout his life – legislator, diplomat, developer, and father. Born into a prominent North Carolina family, Pearson left his mark on the state’s legal and political landscape, while his actions played a role in Asheville’s development for decades.

A lawyer by trade, Richmond Pearson donned many hats throughout his life – legislator, diplomat, developer, and father. Born into a prominent North Carolina family, Pearson left his mark on the state’s legal and political landscape, while his actions played a role in Asheville’s development for decades.

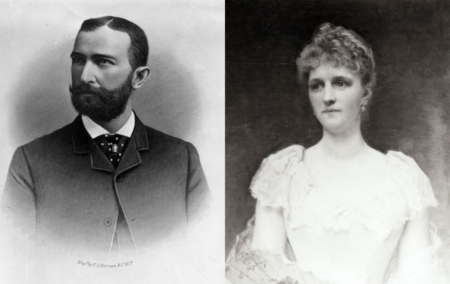

Pearson was born in 1852 at his family’s estate in Yadkin County, also called Richmond Hill. He graduated from Princeton University and studied law under his father Richard Mumford Pearson, Chief Justice of the North Carolina Supreme Court for 20 years. President Ulysses S. Grant appointed Pearson as consul in Belgium from 1874-1877.

When his father died, he returned to North Carolina where he represented Buncombe County in both the state Assembly and House of Representatives. Pearson married tobacco heiress Gabriell Thomas in 1882 and they had four children, two of whom lived to maturity.

Pearson recognized the potential of Asheville, a burgeoning city transformed by the arrival of the railroad. He bought up his siblings’ shares of his father’s Richmond Hill estate in Buncombe County and built a grand Queen Anne style home.

He joined forces with other business leaders to develop Montford, a planned community away from the city center’s hustle and bustle. He even organized a celebratory Fourth of July event in 1890 to promote land development on his own Richmond Hill property where lots were offered in sizes of four to 80 acres.

Pearson’s political career took another turn when he was elected to the U.S. House of Representatives. This eventually led to a series of diplomatic appointments under President Theodore Roosevelt, taking him to Italy, Persia, Greece, and Montenegro.

Richmond Hill’s Second Act

In 1909, Pearson retired from diplomatic service and returned to Richmond Hill in Buncombe County to concentrate on his law practice. He died at his home in 1923 and is buried in Riverside Cemetery. His wife passed away the next year.

The Pearson family offered to sell a portion of the Richmond Hill estate to the City of Asheville for a public park in 1919, an offer that was accepted shortly thereafter. It remained undeveloped for the next eight decades, a victim of Asheville’s $41 million municipal debt following bank failures and the Great Depression.

The Pearson family offered to sell a portion of the Richmond Hill estate to the City of Asheville for a public park in 1919, an offer that was accepted shortly thereafter. It remained undeveloped for the next eight decades, a victim of Asheville’s $41 million municipal debt following bank failures and the Great Depression.

Following their mother’s death, Marjorie and Thomas Pearson traveled and worked around the world, returning to open the Richmond Hill mansion as a museum in 1951. The estate was sold to North Carolina Baptist Homes in 1974 with the stipulation the house be preserved for at least ten years.

Preservation Society of Asheville and Buncombe County then purchased the mansion for $1 and moved it 600 feet onto seven and a half acres of adjacent land. A Greensboro firm purchased the house and 40 additional, adjoining acres in the late 1980s and transformed the mansion into a boutique hotel with a conference center and restaurant. After addition of cottages and other expansions, the property was set to be sold before a fire destroyed the treasured icon in 2009. Today, the remaining grounds operate as OM Sanctuary.

Housing development took off near future Richmond Hill Park in the 1950s and portions of the area were annexed into the City of Asheville. Kavanagh-Smith and Company, one of the largest residential developers in the southeast, built 59 ranch style homes and brick bungalows around Richmond Hill Drive in 1962.

With expansion of city limits, a second municipal golf course proposed for the Richmond Hill property dominated discussions of the day and for years to come. Kavanagh-Smith used its seeming inevitability to promote home sales. While the golf course ultimately failed to materialize, it had support from the community and elected officials. $100,000 from the sale of Rhododendron Park in 1967 was even earmarked for golf course construction.

After little visible progress, Richmond Hill residents petitioned City Council to build the course in 1970, but councilors balked at the estimated $750,000 price tag and suggested working with county government on a golf course and recreation facility. A few years later, a playground and basketball court were proposed for the property.

Shank, Mulligan, Repeat

The debate over Richmond Hill Park’s use came and went for years with golf always in the mix. However, the next time City Council officially took up the issue in 1995, they debated building a youth sports complex or selling the property to raise money for streets and water lines to attract a large office park.

Asheville Parks & Recreation (APR) developed a vision plan that called for major upgrades and additional recreation facilities throughout the city to meet Asheville’s projected needs by 2015. The plan envisioned Richmond Hill Park as a special use park with a golf course, ballfields, soccer fields, football fields, playgrounds, and parking lots. The golf course again proved a controversial part of the plan, but it was argued a necessity to generate revenue that the department could reinvest into the parks and recreation system.

Asheville Parks & Recreation (APR) developed a vision plan that called for major upgrades and additional recreation facilities throughout the city to meet Asheville’s projected needs by 2015. The plan envisioned Richmond Hill Park as a special use park with a golf course, ballfields, soccer fields, football fields, playgrounds, and parking lots. The golf course again proved a controversial part of the plan, but it was argued a necessity to generate revenue that the department could reinvest into the parks and recreation system.

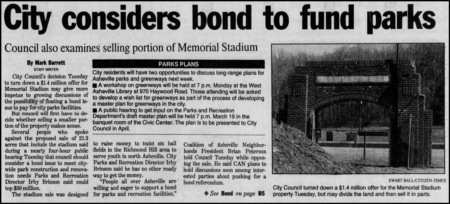

To finance Richmond Hill Park’s development, City leaders proposed selling Memorial Stadium to a group of physicians who wanted to create a medical park on that site. The $1.4 million sale would finance the first phase of Richmond Hill Park and the physicians would also purchase a 100-by-200-foot strip of land owned by former vice mayor Chris Peterson for $75,000 and donate it to the City for public access to Richmond Hill Park.

Community members who lived near Memorial Stadium thought losing one public park to finance another was an unsustainable solution to Asheville’s long-term recreation needs. After nearly four hours of public comment, City Council decided not to sell the stadium and directed APR to prioritize community investment projects from the vision plan and explore general obligation (GO) bonds for funding.

APR scaled down the $57.3 million plan to an $18 million bond package by prioritizing greenways and smaller parks. The plan for Richmond Hill Park included four ballfields with the two largest fields designed to allow football, soccer, and rugby, as well as a concessions and restrooms building, parking, playground, walking and biking trails, picnic shelter, and educational natural areas. During a May 1999 election in which a mere 13.7 percent of registered voters participated, the parks and recreation bond referendum narrowly failed by just 357 votes.

Urban Oasis

APR’s successful development of large projects like Azalea and Carrier parks led to renewed interest in creating Richmond Hill Park. Community members reestablished trails in 2001 that had been originally cleared for carriages in the late 1800s. WNC Disc Golf Association completed a course in the park, only the second disc golf course in the area. UNC Asheville’s cycling club organized trail building and maintenance days and APR offered mountain biking classes and guided hikes by 2002.

APR’s successful development of large projects like Azalea and Carrier parks led to renewed interest in creating Richmond Hill Park. Community members reestablished trails in 2001 that had been originally cleared for carriages in the late 1800s. WNC Disc Golf Association completed a course in the park, only the second disc golf course in the area. UNC Asheville’s cycling club organized trail building and maintenance days and APR offered mountain biking classes and guided hikes by 2002.

However, the park’s path wasn’t without twists. The National Guard approved a move of its armory from Shelburne Road to a section of the park in 2003. Construction of the campus was set to include a public gymnasium and ballfields. Following erosion studies and grading difficulties, APR requested Richmond Hill Park remain a natural area with the exception of the armory. This opened the door for a new vision – a park that embraces Asheville’s love for the outdoors.

After a year of construction, a redesigned Richmond Hill Park reopened in 2007 with wetland setbacks and an environmentally responsible design including a relocated 18-hole disc golf course, new entry road, and parking area. Pisgah Area Southern Off-Road Bicycle Association volunteers began building bike skills areas and multi-use trails that wind through the park today.

After a year of construction, a redesigned Richmond Hill Park reopened in 2007 with wetland setbacks and an environmentally responsible design including a relocated 18-hole disc golf course, new entry road, and parking area. Pisgah Area Southern Off-Road Bicycle Association volunteers began building bike skills areas and multi-use trails that wind through the park today.

The park’s evolution continued when 77 percent of Asheville voters approved a $17 million GO bond referendum in 2016 to address deferred maintenance and upgrade parks throughout the city. $520,000 was earmarked to improve Richmond Hill Park with four-season restrooms, covered picnic areas, expanded greenspace, and new walkways connecting park features.

The full property remains largely undeveloped, but continues to become an even greater urban oasis as new trails open and further refinement of the disc golf course. Richmond Hill Park’s story is a testament to Asheville’s dynamic spirit as a place where the past informs the present – and where the community’s collective creativity shapes a space for all to enjoy.

Do you have photos or stories to share about Richmond Hill Park? Please send them to cbubenik@ashevillenc.gov so APR can be inspired by the past as we plan our future.

Photo and Image Credits

- Lithograph reproduction titled “French Broad from Richmond Hill” removed from Land of the Sky, Views on the Western North Carolina R.R., published in 1883-1884 by Chisholm Brothers of Portland, Maine. This view faces north toward Craggy Railroad Bridge with tracks along the right riverbank. Courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

- Portrait of Richmond Pearson from engraving by F.G. Kerman and Company of New York City. Portrait painting of Gabrielle Thomas Pearson by unknown. Courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

- Photo postcard showing Richmond Hill Inn, probably taken in the late 1990s, shows the Inn brightly lit at night. Postcard donated by Sharon Fahrer. Courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

- Greensboro-based Kavanagh-Smith and Company targeted middle class homebuyers as they established neighborhoods throughout the southeast. In the Asheville area, they developed Richmond Hill and Knollwood/Skyview Terrace in West Asheville, Parkway Forest in Oteen, Bent Creek on the former Bent Creek Ranch property off Brevard Road, and others. Ad from April 7, 1963 edition of Asheville Citizen-Times.

- To repair, maintain, and expand a deteriorating park system, the City of Asheville asked voters to approve an $18 million GO bond package in 1999. The measure fell short in a special election with dismal participation. APR secured state, federal, and private financing for several large projects over the next decade; when management of Recreation Park, Aston Park Tennis Center, Western North Carolina Nature Center, and Asheville Municipal Golf Course reverted back to the City from Buncombe County, it was clear a reliable funding stream was necessary. Voters overwhelmingly approved a $17 million GO bond referendum in 2016 to address deferred maintenance, add major enhancements, and acquire land for investments throughout the city. Article from March 12, 1998 edition of Asheville Citizen-Times.

- Since Richmond Hill Park opened, PSORBA volunteers have collaborated with APR to expand access for bikers, hikers, and trail runners.

- A picnic shelter and four-season restrooms were added as part of GO bond-funded improvements.