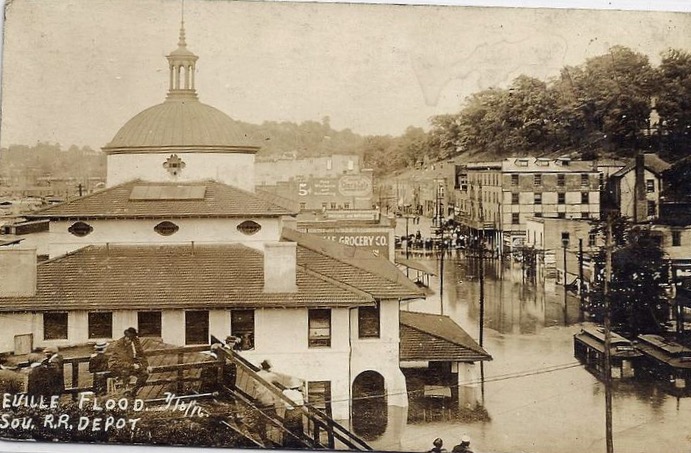

By any measure Asheville’s catastrophic Flood of 1916 stands as “The Flood by Which All Other Floods Are Measured.”

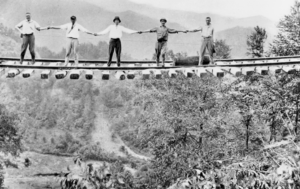

When two tropical storms converged on the mountains in tandem that summer — one from the Gulf in June followed by another from the Atlantic in July — the water that thundered in its wake wasn’t just “high;” it carved away the ground under mountain railroad passes, leaving tracks looking like sky-high trapeze rigs hanging 20 to 60 feet in the air.

Dams breached. Eighty people died.

Never before had so much rain fallen anywhere in the United States in a 24-hour period, the National Weather Bureau reported.

The French Broad River, usually about 380 feet wide, stretched 1,300 feet across. It crested at 21 feet, some 17 feet above flood stage. Though the rain had stopped on the Sunday morning of July 16, 1916, people were taken by surprise by the speed and volume of rising floodwaters. Many resorted to climbing into and clinging to trees during the deluge. Some of them saw friends and family member slip away when they couldn’t hold on any longer.

Asheville’s power plant was destroyed. With tracks severely damaged, the railroad was dead in the water.

After the flood receded, an apocalyptic landscape ravaged by mudslides revealed destroyed homes and industries. Asheville contact with the outside world was cut off.

(Photograph courtesy of the State Archives of North Carolina)

One hundred years after the Flood of 1916, Asheville collectively wonders, “Can it happen again?”

The answer is yes. And no.

Modern meteorology now gives advance notice of major rain events. “Today FEMA has mapping systems that can predict how much rainfall we are going to get, and which areas are going to be flooded,” said Kelley Klope of the Asheville Fire Department. “The City can help notify people ahead of time through its Everbridge emergency notification system (called Citizens Alert), announcements to local media and messages on our social media channels.”

The City of Asheville has detailed emergency preparedness plans in place, procedures for monitoring river flow and managing capacity at the North Fork Dam.

The City’s Stormwater Services Division plays an active role in monitoring runoff patterns and developing systems to manage that water. “What we do is provide mitigation to the depth of flooding, but this an area subject to flooding — and it will flood again,” said McCray Coates, Stormwater Division Manager.

In his job, Coates oversees installation and maintenance of Asheville’s stormwater control infrastructure. The Azalea Road and Craven Street projects are example of recent stormwater projects, which include stream restoration and construction of stormwater management structures along the Swannanoa and French Broad Rivers. Coates also works closely with the Army Corps of Engineers to develop flood mitigation projects for the City.

Completed in 2015, the Azalea Road project was “designed to mitigate flooding and provide stream restoration below the dam and capacity above,” said Coates.

The Asheville Fire Department, which was a small unpaid volunteer force 100 years ago, now has 30 firefighters trained in advanced swift water rescue. All Asheville firefighters have training in basic swift water rescue training.

Still, the force of nature continues to impact Asheville with recurring floods. “About every 20 years we have a major flooding event,” Coates noted.

In 2004, virtually the same scenario walloped Asheville when Tropical Storms Ivan and Frances converged upon Western North Carolina, producing the wettest September ever recorded. Again, Ivan came up from the Gulf, followed by Frances for another double tropical storm wallop. Frances alone dropped 23 inches of rain on some parts of WNC. When the storms hit, Asheville’s North Fork Reservoir was full. For safety reasons, some of the water had to be released.

Unfortunately, 11 people died in Western North Carolina during the 2004 floods. One hundred forty homes were destroyed, another 16,234 damaged. There was $7 million dollars in damage in a seven-county area. It served as a sobering reminder of what can happen, even today.

In the wake of the flood of 2004, Asheville updated its flood plan with an eye toward careful management of the amount of water in the North Fork Reservoir, Asheville’s 22,000 acres of pristine, protected watershed. The plan is designed to manage storage within the reservoir, and considers seasonal factors such as rain events and the vegetative cover within the watershed, according to Water Resources Director Jade Dundas.

Water can be released from the reservoir in advance of major rainfall forecasts. That builds in capacity in the North Fork Reservoir to lessen the need to release water during a major weather event. Even so, “the dam was never designed for flood mitigation,” according to Leslie Carreiro, Water Production/Quality Division Manager. It was designed to provide water for the City of Asheville.

Stream gauges now installed above and below the reservoir help inform release decisions. While portions of Biltmore Village flooded 4 feet deep during the flood of 2004, inundation maps showed only 2 or 3 inches of the Biltmore Village flooding came from the reservoir.

(Photograph by Steve Nicklas, NOS, NGS; courtesy of National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration/Department of Commerce)

A lot of factors affect flooding here in the mountains: topography not the least of them. Water from the mountains’ many unnamed streams feed into creeks that feed into rivers.

And Asheville’s increasing level of development has been a “game changer,” according to Public Works Director Greg Shuler. Increased development results in increased impervious surfaces like rooftops and asphalt that do not absorb rainwater. That produces more runoff and along with it the need for more stormwater management systems in Asheville.

Following the flood of 2004, the Army Corps of Engineers developed an emergency action plan for Biltmore Village. A flood ordinance was revised in 2010, mandating that new buildings have to be 2 feet above base elevation. That’s why you see the newer shops in Biltmore Village built on structures above the street level.

There is enhanced communication between emergency agencies locally, regionally and on the federal level with the Federal Emergency Management Agency, FEMA.

Today, preparedness serves as the cornerstone for the City of Asheville. For example, the Water Resources Department recently did a tabletop exercise with local emergency management officials and City dam design consultant Schnabel Engineering on the scenario of a breach at the North Fork Dam, which would be a catastrophic event. Regional fire departments and the Buncombe County Sheriff’s Office participated.

Changes were completed at North Fork Dam in 2020 as part of an emergency action plan update from the state. Engineers are crafting plans to raise and reinforce the dam another 4 feet. This will not only enhance the dam’s integrity but also add capacity.

“As we add more capacity for storage, we don’t have to adjust the levels for water as often,” said Lee Hensley, Maintenance Supervisor for Water Production.

When there is a major rain event and water needs to be released, the Water Resources Department contacts Buncombe County Emergency Management. “If we’re filling up, almost full, we’re going to need to open the gates,” said Hensley. Sometimes water has to be released to ensure that the dam stays intact.

When floods come, Asheville’s Fire Department and Public Works Department are well equipped for rescue and recovery.

The Asheville Fire Department has two large inflatable rafts and three motorized rafts. Every fire truck has personal flotation devices on them along with ropes and throwbags used to pull someone caught in swift water to safety, said Klope.

“All firefighters today are trained in a basic level of swift water rescue,” Klope added. “We have approximately 30 personnel who are trained to a specialist level in swift water rescue.” AFD also has 30 certified divers on staff.

During weather emergencies, AFD increases staffing to provide the best possible response and coverage. “We strive to be proactive and to notify residents so they can be prepared,” Klope said.

“During a flood, a lot of our rescues are from cars, people who have driven into flooded waters,” Klope added.

That’s where the Public Works Department comes in. They and the Asheville Police Department work quickly to put up barricades on flooded roads or where waters are swiftly rising.

After a storm the City’s Public Works Department is charged with cleaning up debris and removing fallen trees on our roads. “Recovery is where we come into play,” said Public Works Director Greg Shuler. “Our crews work on removing large debris fields and repairing streets, sidewalks and embankments that have failed and roadway failures. A lot of times the first thing to go is underground infrastructure, like pipes and storm drains.”

Landslides that block roads are often an issue in addition to flooding, blocking roads. “It’s a byproduct of the ground saturation and terrain in our region,” Shuler said.

We know that climate change can bring more frequent and stronger weather events. The floods will come. Whether it’s through City policy on building in flood zones, updating the City’s flood action plan or ensuring special rescue training for first responders, the City of Asheville takes a multiple pronged approach to ensuring safety for its residents.

“From historic knowledge and experience, the City of Asheville uses its flood operations plan in anticipation of a major rain event,” notes Dundas.

Those plans, coupled with an unprecedented ability to notify residents of imminent danger through mobile phone technology and computers, greatly lessens the risk of a catastrophic loss of life when major flooding comes to call. And based on both history and future meteorology modeling, it will.

NOTE: This article was written in 2017 and some people quoted now work in different positions. Also the symposium and exhibit listed below happened in 2017.

Centennial flood symposium and exhibition

FLOOD SYMPOSIUM AND COMMEMORATION OF THE GREAT FLOOD OF 1916:

Set for July 15-16 at A-B Tech’s Ferguson Auditorium this free symposium will explore the flood’s short-term and long-term impacts on Asheville. Discussion will also center on what lessons we’ve learned in emergency management in the past 100 years. Asheville’s Stormwater Services Manager McCray Coates will participate on a panel discussion from 1:30-3:30 p.m. July 15 focused on the addressing the question, “Are we prepared for the next flood?”

FLOOD OF 1916 EXHIBIT:

North Carolina Office of Archives and History’s exhibit, “So Great the Devastation: The 1916 Flood,” is on display at Pack Library through July 15. The exhibit features archival photos and accounts of the event.