This entry is part of Park Views, an Asheville Parks & Recreation series that explores the history of the city’s public parks and community centers – and the mountain spirit that helped make them the unique spaces they are today. Read more from the series and follow APR on Facebook and Instagram for additional photos, upcoming events, and opportunities.

In the aftermath of the devastating Flood of 1916, Asheville’s riverfront faced a decades-long period of neglect. However, a determined community effort would eventually transform this once-forgotten area into a vibrant hub of recreation, social activity, and economic growth with French Broad River Park serving as a major stimulus of the city’s river renaissance.

Where Rivers Meet

Modern day Buncombe County was originally inhabited by ᏣᎳᎩ, romanized as Anigiduwagi and more commonly known as the Cherokee (ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ) people. ᏙᎩᏯᏍᏗ (Togiyasdi, “the place where they race”) was the name given to the joining of the French Broad and Swannanoa rivers by the Cherokee people as they built towns and villages, complete with meeting plazas, hunting grounds, racetracks, and courts for ball play along the riverbanks.

Modern day Buncombe County was originally inhabited by ᏣᎳᎩ, romanized as Anigiduwagi and more commonly known as the Cherokee (ᎠᏂᏴᏫᏯᎢ) people. ᏙᎩᏯᏍᏗ (Togiyasdi, “the place where they race”) was the name given to the joining of the French Broad and Swannanoa rivers by the Cherokee people as they built towns and villages, complete with meeting plazas, hunting grounds, racetracks, and courts for ball play along the riverbanks.

When Spanish conquistador Hernando de Soto passed the rivers’ confluence during his search for gold in 1541, he encountered big towns, well-used roads, and abandoned homes. A smallpox epidemic — one of a series of plagues carried from Europe — had decimated the native people. One Spanish writer in his expedition noted, was a public walk, “along which six men could pass abreast.”

After 1783, white settlers could apply for land grants and the Woodfin, Rankin, Patton, McDowell, Smith, and other families colonized the area’s first large farms and plantations. Asheville later transformed itself from a livestock town of stockyards to a center of commerce, industry, and tourism with the railroad’s arrival in 1880. For the next few decades, the riverfront district operated as one of the area’s primary industrial areas due to its proximity to the railway.

A new courthouse was completed in 1887 that included a third-story opera house and the city’s early developers began to take notice of the emerging middle class. Asheville Electric Company opened Riverside Park in 1904, a popular spot on the French Broad near Pearson Bridge with a horse track, lake, ballfield, casino, and amusement rides. Electric streetcars connected the park and bustling riverfront with Pack Square, Aston Park, and other affluent areas of the growing city.

The Flood of 1916 jumped the banks of the French Broad and Swannanoa and washed away Riverside Park, as well as businesses and residences along the riverfront. With rapid growth in the early 20th century, Asheville was the third largest city in North Carolina and the City of Asheville’s 1922 plan envisioned a city of parks, plazas, and parkways including a riverway park and greenbelt along the French Broad and Swannanoa rivers.

However, Ashevillians would not enjoy a river park anytime soon. In 1930, local banks failed, saddling Asheville with $41 million in debt – more than the debts of Raleigh, Durham, Greensboro, and Winston Salem combined. An epic spending spree brought an unprecedented number of publicly-funded projects including Recreation Park, Asheville Municipal Golf Course, McCormick Field, Memorial Stadium, and several others.

To prevent further liabilities, no new debts could be incurred unless they were approved by a majority of voters in a referendum. For this reason, the park system remained largely stagnant for the following decades.

A New Vision for the French Broad

By the 1950s, Asheville’s population growth turned the French Broad into an open cesspool in the form of floating sewage, garbage disposal, industrial and chemical runoff, and landfill seepage. Residents and businesses left the riverfront behind to auto graveyards, junkyards, abandoned buildings, and rundown factories that straight-piped waste directly into the river. Pollution was so bad that it was considered a “dead river” and several native fish and aquatic species became extinct.

By the 1950s, Asheville’s population growth turned the French Broad into an open cesspool in the form of floating sewage, garbage disposal, industrial and chemical runoff, and landfill seepage. Residents and businesses left the riverfront behind to auto graveyards, junkyards, abandoned buildings, and rundown factories that straight-piped waste directly into the river. Pollution was so bad that it was considered a “dead river” and several native fish and aquatic species became extinct.

Wilma Dykeman’s first book, The French Broad, was released in 1955. The collection of stories depicting historical events connected to the river included chapters about the Civil War, formation of Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), and biographies of colorful characters alongside those covering pollution and water contamination. By connecting clean air and water with economic development and human well-being, Dykeman stressed the importance of understanding history and using that knowledge to go forward.

In 1961, TVA proposed building a series of 14 hydroelectric dams in the French Broad watershed that would have flooded more than 18,000 acres of mountain valleys including the Warren Wilson College farm. While the $100 million project had near universal acceptance among local government leaders, a grassroots group of “dam fighters” organized as the Upper French Broad Defense Association, waging a multiyear campaign against the massive project.

The group demanded that TVA hold public hearings, which lasted for three days in Asheville and were attended by hundreds of people who donned homemade yellow scarves in protest. TVA abandoned the plan; in the process, the community decided to embrace the river, setting the stage for a French Broad rebound.

In 1976, Land of Sky Regional Council obtained a small grant from TVA to begin a regional approach to long range planning for the French Broad River. Over the next decade, river cleanup efforts and the annual French Broad River Week festival led to the discussions with organizations like Quality Forward (now Asheville Greenworks) about long-term planning for the river’s future. Around the same time, artists and creators began moving into the Asheville riverfront’s vacant industrial buildings and transforming them into large and small studios.

Meeting at the Confluence Again

When Asheville Area Chamber of Commerce was looking for a short-term project manager to develop a riverfront master plan in 1986, they hired Karen Cragnolin. She says she spent most of the first day trying to figure out how to actually get down to the French Broad. With a $10,000 grant from the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation, Cragnolin, members of the Riverfront

When Asheville Area Chamber of Commerce was looking for a short-term project manager to develop a riverfront master plan in 1986, they hired Karen Cragnolin. She says she spent most of the first day trying to figure out how to actually get down to the French Broad. With a $10,000 grant from the Z. Smith Reynolds Foundation, Cragnolin, members of the Riverfront  Attractions Committee, and Asheville Parks & Recreation (APR) scheduled a series of charrettes and brainstorming sessions to explore possibilities for river use.

Attractions Committee, and Asheville Parks & Recreation (APR) scheduled a series of charrettes and brainstorming sessions to explore possibilities for river use.

The riverfront development plan concluded that if people actually got to the river, they would see its potential. French Broad River Foundation resulted at this time, as well as a group of esidents known as “River Links” whose primary focus was the French Broad within Asheville city limits. Eventually, the group became the local nonprofit RiverLink.

Jean Webb Park opened on the east side of the French Broad in 1988 and momentum continued to bring a larger park to the west bank. After years of talks and building relationships, Carolina Power & Light (now Duke Energy) conveyed several acres along the river to the City of Asheville. The site had been used as an unauthorized dump for household garbage and other items including cinder blocks, mattresses, and television sets.

Following an archaeological study and hazardous waste testing, construction began in 1993 and was broken into three phases. The first phase included a paved riverwalk greenway with overlooks, restrooms, playground, benches, and gazebo. The greenway and park would extend southwest (now Amboy Riverfront Park) in the next planned phase and to the Haywood Road bridge (now RiverLink Bridge) in phase three. An additional phase added and linked Carrier Park to French Broad River Park many years before phase three was completed.

Following an archaeological study and hazardous waste testing, construction began in 1993 and was broken into three phases. The first phase included a paved riverwalk greenway with overlooks, restrooms, playground, benches, and gazebo. The greenway and park would extend southwest (now Amboy Riverfront Park) in the next planned phase and to the Haywood Road bridge (now RiverLink Bridge) in phase three. An additional phase added and linked Carrier Park to French Broad River Park many years before phase three was completed.

2,000 people gathered for French Broad River Park’s dedication on September 25, 1994. Features included an observation deck with river views, “striking restroom building” and picnic gazebo inspired by Riverside Park, stone fishing platform, rolling lawns, swings, picnic tables, and grills – all designed to withstand flooding. The weathervane atop the gazebo featured a blue herring, an avatar for the park of symbol of life returning to Asheville’s riverfront. Local garden clubs planted 1,000 feet of wildflower beds throughout the park.

French Broad River Greenway also got its start with less than a quarter of a mile of paved surface in the park. RiverLink and other community organizations continued fundraisers such as Fall in Love with the French Broad Caberet and sunset wine and cheese “cruises” in canoes and rafts from the park. New Asheville Motor Speedway, located nearby, hosted Rockin’ on the River with proceeds from that concert and a corresponding album benefiting the park.

Thanks to these efforts, an outdoor classroom and additional 0.34 miles of greenway opened in 1996. Asheville’s first dog park opened within French Broad River Park in 2001, a feature just as popular as the greenway in the park that now stretches from Craven Street to Hominy Creek River Park.

French Broad River Greenway

Now the city’s longest greenway, French Broad River Greenway started with the park’s two sections, proving even transformative projects start small. Today, greenways are a hotspot for Asheville’s avid and amateur cyclists, runners, dog walkers, roller skaters, residents, and visitors.

Now the city’s longest greenway, French Broad River Greenway started with the park’s two sections, proving even transformative projects start small. Today, greenways are a hotspot for Asheville’s avid and amateur cyclists, runners, dog walkers, roller skaters, residents, and visitors.

By the late 1980s, cities and towns began building “linear parks” along roads, rivers, and parkways for recreation, transportation, and economic benefits. Eager to share innovative ideas and show quick progress on its riverfront,  Asheville hosted the third Parkways, Riverways, and Greenway Conference in 1989 with guided tours of the French Broad and Blue Ridge Parkway. Of course, another goal for hosts was showing local decision makers that greenways were a big deal that they should embrace.

Asheville hosted the third Parkways, Riverways, and Greenway Conference in 1989 with guided tours of the French Broad and Blue Ridge Parkway. Of course, another goal for hosts was showing local decision makers that greenways were a big deal that they should embrace.

A long-discussed river whitewater training course along the greenway was also proposed, but the flow of the river was not conducive. Buncombe County developed Ledges Whitewater  River Park to support the area’s paddling scene, part of what Paddler magazine recognized as one of the best youth instructional programs in the country.

River Park to support the area’s paddling scene, part of what Paddler magazine recognized as one of the best youth instructional programs in the country.

French Broad River Greenway started as 0.19 miles in French Broad River Park in 1994, growing another 0.34 miles in 1996. It extended 0.35 miles to Amboy Riverfront Park in 1998. Two sections were added within Carrier Park in 2002 and 2006, each 0.3 miles long. In 2010, 1.2 miles was added to link Hominy Creek River, Carrier, Amboy Riverfront, and French Broad River parks.

After a short break, the section between Craven Street and Haywood Road opened. A nearly one mile section opened in 2023, linking French Broad River Park to Haywood Roadand fulfilling phase three from the park’s original plan nearly 30 years before.

After a short break, the section between Craven Street and Haywood Road opened. A nearly one mile section opened in 2023, linking French Broad River Park to Haywood Roadand fulfilling phase three from the park’s original plan nearly 30 years before.

Do you have photos or stories to share about French Broad River Park and French Broad River Greenway? Please send them to cbubenik@ashevillenc.gov so APR can be inspired by the past as we plan our future.

Photo and Image Credits

- The iconic gazebo is an original feature of the park.

- A circa 1917 aerial view of French Broad River with West Asheville Bridge in foreground and Smith Bridge and Southern Railway Bridge in background. Courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

- Color photo offset showing a young woman standing beside a smooth flowing French Broad River, circa 1950s. Courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

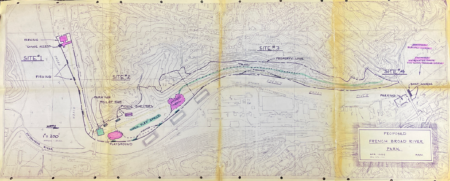

- Original plans for French Broad River Park show three phases. Extension of the greenway to Haywood Road was completed in 2023.

- A bollard displays the logos of the City of Asheville and RiverLink.

- French Broad River Park is the site of Asheville’s first greenway and first dog park.

- A family takes a break from biking to admire the river.

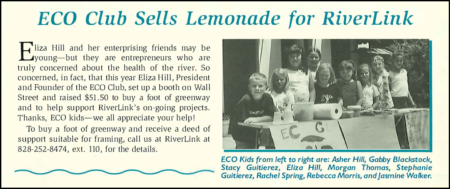

- Community members could symbolic buy a section of greenway – complete with a “deed” – one of many fundraisers that contributed to its completion. Even enterprising kids got in on the real estate deal!

- Mayor Terry Bellamy cut the ribbon on a section of French Broad Greenway connecting Carrier and Hominy Creek River parks.

- French Broad River Park hosted French Broad River Sculpture Festival along the park’s section of greenway in the late 2000s.