This entry is part of Park Views, as Asheville Parks & Recreation series that explores the history of the city’s public parks and community centers – and the mountain spirit that helped make them the unique spaces they are today. Read more from the series and follow APR on Facebook and Instagram for additional photos, upcoming events, and opportunities.

By the end of the 1990s, Asheville adopted its first greenways plan and about a mile of completed greenways under its belt. As important links in the city’s transportation network and recreational offerings, Glenn’s Creek and Reed Creek greenways are products of partnerships and community spirit with roots spanning centuries.

Buncombe Turnpike

The Asheville area experienced slow, but steady growth following arrival of the first European settlers with around 1,000 residents counted by the first United States Census in 1790. This number excluded the Cherokee who inhabited the region for thousands of years prior and built villages along the Swannanoa and French Broad rivers whose confluence was called ᏙᎩᏯᏍᏗ (Untokiasdiyi or Togiyasdi, “the place where they race”).

The Asheville area experienced slow, but steady growth following arrival of the first European settlers with around 1,000 residents counted by the first United States Census in 1790. This number excluded the Cherokee who inhabited the region for thousands of years prior and built villages along the Swannanoa and French Broad rivers whose confluence was called ᏙᎩᏯᏍᏗ (Untokiasdiyi or Togiyasdi, “the place where they race”).

While trappers and frontiersmen used Cherokee trails and paths left by wild animals to navigate gorges and peaks in the mountains, they were largely insufficient for homesteaders and traders moving goods to market. As the foothills of Tennessee became major areas for raising cows, sheep, fowl, and hogs, a more efficient way to move livestock to more populated coastal cities including Charleston and Augusta was needed.

In 1819, the North Carolina General Assembly created the Board of Internal Improvements to build roads for improvement of trade and regional growth. The construction of Buncombe Turnpike came from the board’s plans to link two separate towns named Greenville in Tennessee and South Carolina. Completed in 1828, it brought new settlement, commercial trade, and tourism to western North Carolina.

The 75-mile artery roughly followed the same path as present-day U.S. 25 through Buncombe County, joining the gentle grade of the French Broad near today’s Riverside Drive. As summer visitors from the coast traveled to Asheville in the comfort of carriages instead of wagons, points along the turnpike developed into popular resorts and boarding houses among small fields owned by local farmers.

Just as trails the Cherokee established along waterways and through forests for travel, food gathering, recreation, and commerce eventually turned into stagecoach trails like the Buncombe Turnpike, they in turn welcomed railroads, street car tracks, and eventually modern roads and greenways.

On Broadway

Broadway has changed substantially over the years. European Americans began to settle in the Asheville area after the United States gained independence in the American Revolutionary War. Buncombe County officially formed in 1792 and the county seat was established near modern day Pack Square where two Cherokee trails crossed in 1793. Originally named Morristown, it was incorporated as Asheville in 1797. Named for North Carolina Governor Samuel Ashe, the name change was a strategic play to gain favor with state lawmakers.

Broadway has changed substantially over the years. European Americans began to settle in the Asheville area after the United States gained independence in the American Revolutionary War. Buncombe County officially formed in 1792 and the county seat was established near modern day Pack Square where two Cherokee trails crossed in 1793. Originally named Morristown, it was incorporated as Asheville in 1797. Named for North Carolina Governor Samuel Ashe, the name change was a strategic play to gain favor with state lawmakers.

The first lot on record sold in the city by developer John Burton was to his brother, Thomas, in 1794 for 20 shillings for a “lot of land on the west side of main street.” Since this was the only street in town, other early deeds simply refer to it as “the street.” Until 1914, the roads today known as Biltmore and Broadway were named South Main Street and North Main Street, respectively.

With 14,694 inhabitants in 1900, Asheville was the third largest city in North Carolina and would grow to 50,000 by 1930. During this short-lived, rapid growth spurt, neighboring towns including West Asheville, Kenilworth, and Biltmore Forest also grew in popularity. Perhaps to stake its claim as the economic and cultural center of western North Carolina, Asheville widened many of its primary streets and renamed North Main Street to Broadway. Shops along the thoroughfare immediately began advertising “Broadway style” clothing and manufactured goods.

The street includes a suffix to better respond to emergency calls, officially Broadway Street. However, it has also been named Broadway Avenue in some City of Asheville documents and most locals simply call it Broadway.

Widening Broadway and Asheville’s First Greenways

Broadway was further impacted by the construction of I-240, the growth of neighborhoods to the north of the freeway, downtown revitalization plans, and urban renewal projects. Some community members advocated for the widening of Broadway from two to four lanes between downtown and UNC Asheville as early as the 1970s, but the conversation became a prominent topic of interest when the Strouse, Greenberg, and Company downtown mall complex proposal gained support among elected officials.

Broadway was further impacted by the construction of I-240, the growth of neighborhoods to the north of the freeway, downtown revitalization plans, and urban renewal projects. Some community members advocated for the widening of Broadway from two to four lanes between downtown and UNC Asheville as early as the 1970s, but the conversation became a prominent topic of interest when the Strouse, Greenberg, and Company downtown mall complex proposal gained support among elected officials.

In the “most feasible” version of the plan, Broadway would widen to five lanes and serve as the main artery to parking decks for the proposed center. City of Asheville transportation planners noted major improvements needed as intersections at Merrimon Avenue and Chestnut Street were already high accident areas. Ultimately, the mall proposal was defeated and the City of Asheville established the Downtown Development Office to accelerate revitalization of the central business district.

However, calls to widen Broadway did not go away. As biking, walking, jogging, skating, and other forms of human-powered transportation gained momentum as recreational activities, the idea to separate these modes from vehicular lanes became part of the conversation.

City Council officially approved a resolution to widen the northern section of Broadway in 1988. When a municipal agreement with the North Carolina Department of Transportation (NCDOT) was signed in 1992, the City of Asheville “requested, and [NCDOT] agreed, to make every attempt to acquire certain excess right of way or residue properties located along the project needed by the Municipality for a proposed greenway to be constructed adjacent to the project” with the City of Asheville paying for right of way acquisitions. NCDOT agreed to install sidewalks on the east side of Broadway from I-240 to W.T. Weaver Boulevard and between Catawba Street and W.T. Weaver where no sidewalks existed.

Inclusion of this language was in no small part the result of active, engaged community members – many of whom helped create Asheville Greenways Commission, Asheville Parks and Greenways Foundation, and other organizations dedicated to connecting residents with parks, greenways, and recreation opportunities. Another community organization, RiverLink, led the charge to establish the city’s first stretch of greenway, 0.19 miles that opened in French Broad River Park in 1994. That small section expanded another 0.34 miles in 1996 to ultimately become the city’s longest greenway running between Buncombe County Parks & Recreation’s Hominy Creek River Park through multiple APR parks and RiverLink’s Karen Cragnolin Park to Craven Street.

Glenn’s Creek Greenway

With the first greenway open and another planned as part of the Broadway widening project, APR planners and community members looking for ways to expand the greenway network turned to UNC Asheville, which agreed to provide land along W.T. Weaver Boulevard.

With the first greenway open and another planned as part of the Broadway widening project, APR planners and community members looking for ways to expand the greenway network turned to UNC Asheville, which agreed to provide land along W.T. Weaver Boulevard.

The first 0.4 mile section of Glenn’s Creek Greenway opened between Barnard and Merrimon Avenues in 1997 as a partnership between the university, city government, and community members. The immediate popularity of the greenway led NCDOT to join the partnership for the next phase.

At the time, more speeding tickets per mile were written to drivers along W.T. Weaver Boulevard than any other city street. Looking to calm traffic and make the entrance to UNC Asheville more inviting, sections of the boulevard were reduced from four to two lanes, landscaped medians installed, and the city’s first roundabout put in place. Students and community members removed invasive species and replaced them with native woody vegetation to  mitigate urban impacts along the creek.

mitigate urban impacts along the creek.

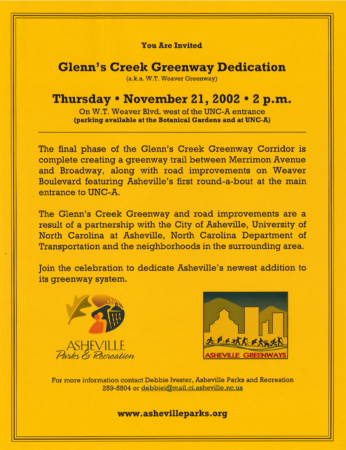

Included in the improvements was another 0.35 mile section of greenway from Barnard Avenue to Broadway that opened in 2002. A crosswalk connected to sidewalks along Broadway in anticipation of the future Reed Creek Greenway that would fully separate pedestrian and bike traffic from vehicle travel.

During a stream restoration project, the Rhoades Trust donated an additional half acre of land to extend Glenn’s Creek Greenway into Weaver Park, connecting the Botanical Gardens at Asheville, the university, and the park to Murdock Avenue. The Rhoades family previously donated land for the university, the park, and W.T. Weaver Boulevard.

In 2023, the section of greenway inside the park got a slight realignment when a new pedestrian bridge replaced one with a steep ramp at the creek crossing.

Reed Creek Greenway

While Glenn’s Creek Greenway came together fairly quickly (for a government improvement project, at least), Reed Creek Greenway’s path was a bit longer. As part of the federal Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA-21)’s Recreational Trails Program, the City of Asheville received $30,000 to begin the planning process for a greenway adjacent to Broadway in 1999. Early community meetings started with a presentation titled, “What is a Greenway?”

While Glenn’s Creek Greenway came together fairly quickly (for a government improvement project, at least), Reed Creek Greenway’s path was a bit longer. As part of the federal Transportation Equity Act for the 21st Century (TEA-21)’s Recreational Trails Program, the City of Asheville received $30,000 to begin the planning process for a greenway adjacent to Broadway in 1999. Early community meetings started with a presentation titled, “What is a Greenway?”

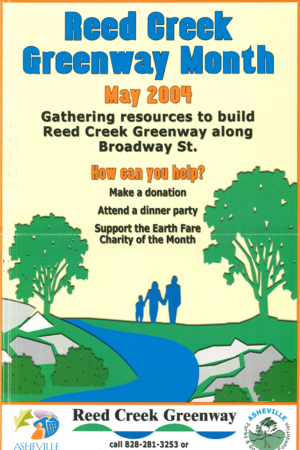

Land purchases and donations of easements for the greenway were obtained by 2004. Coupled with funding from federal and state transportation and clean water grants, foundation funds, private donations, and local tax dollars, work began in earnest after many years of planning. That year, the month of May was named Reed Creek Greenway Month with a goal to raise $35,000 through dinner parties, silent auctions, concerts, and corporate donations for two pedestrian bridges and inform the community about educational stations, public art, wetland biofilter areas, and other features planned for the greenway.

Several volunteers helped prepare the stretch for the accessible, hard surface path in the following years. Metropolitan Sewerage District installed a new sanitation line along the creek, a strategic move to save work to cut the trail’s path, and a 0.19 mile section of the greenway opened in 2006 between Catawba and Cauble streets. The City of Asheville secured the final tract of land for Reed Creek Greenway that same year from The Health Adventure, an interactive children’s facility focused on health.

The Health Adventure was planning to move from Pack Place in downtown Asheville to Broadway and rebrand as Momentum, a new museum with indoor and outdoor exhibits to expand their mission and become a broadly based science museum emphasizing environmental health. The City of Asheville conveyed 1.14 acres on the corner of Broadway and Catawba Street to the museum in exchange for property fronting Broadway.

The museum cleared and graded the property for its new campus, but filed for bankruptcy in 2011 and moved to Biltmore Square Mall. It permanently closed after 45 years of operation when the mall became an outlet shopping center in 2013. North Carolina state government now owns the nearly 10-acre campus that was slated to become Momentum.

The museum cleared and graded the property for its new campus, but filed for bankruptcy in 2011 and moved to Biltmore Square Mall. It permanently closed after 45 years of operation when the mall became an outlet shopping center in 2013. North Carolina state government now owns the nearly 10-acre campus that was slated to become Momentum.

As part of state government, UNC Asheville remained instrumental in expanding Reed Creek Greenway over the next decade. The northern expansion was dedicated in 2014 and further expanded south towards downtown to Elizabeth Street as private development expanded along the Broadway corridor.

Recently, French Broad River Metropolitan Planning Organization provided a grant for a feasibility study to extend Reed Creek Greenway to Riverside Drive to the north and Clingman Avenue to the northwest, providing more links in the chain of Asheville’s greenway network.

Do you have photos or stories to share about Glenn’s Creek Greenway or Reed Creek Greenway? Please send them to cbubenik@ashevillenc.gov so APR can be inspired by the past as we plan our future.

Photo and Image Credits

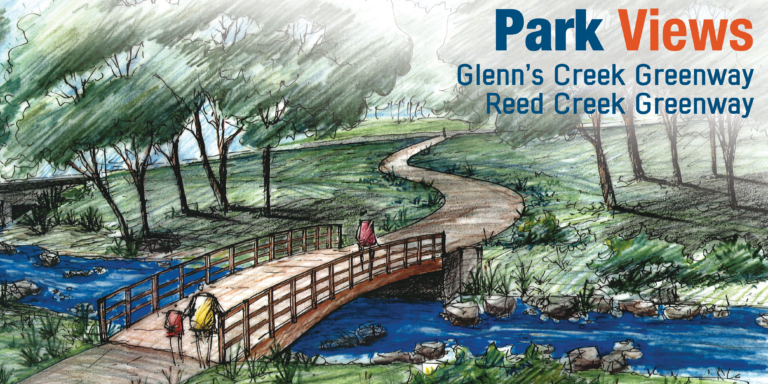

- Rendering of bridge near Catawba Street as part of Reed Creek Greenway Phase 1 from April 2004. The greenway actually runs along a tributary that joins Reed Creek further north. Reed Creek’s headwaters originate on Sunset Mountain. Glenn’s Creek was the site of the first gristmill in western North Carolina which was owned by John Burton, the developer who sold the first recorded lot in Morristown.

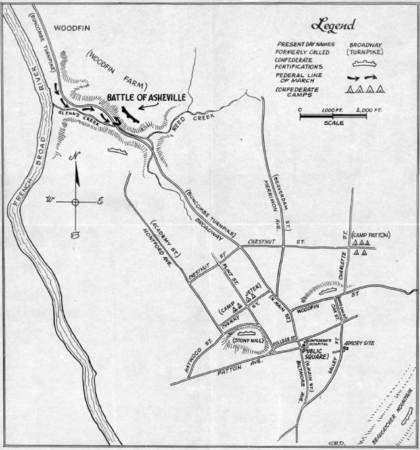

- Undated map showing the Battle of Asheville with Broadway running north towards French Broad River. Glenn’s Creek, Reed Creek, and Buncombe Turnpike are labeled. Today’s Broadway began as North Main Street in Public Square (now Pack Square) and continued without interruption along the old Buncombe Turnpike. Courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

- This ad from The Asheville Gazette-News promotes high end clothing from Morgan N. Smith, a “Broadway Style Shop.” The Langren opened in 1912 and was razed in 1964, serving as as a parking deck until AC Hotel opened on the site in 2017.

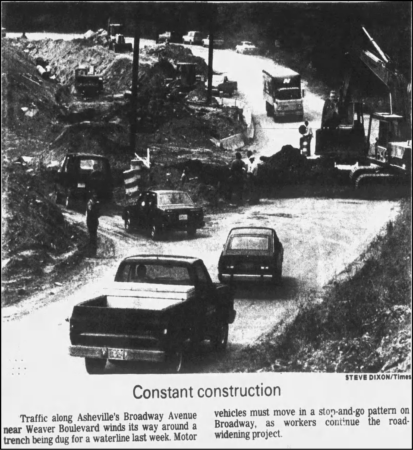

- Even though the Strouse, Greenberg, and Company downtown mall proposal failed, many community members wanted Broadway to serve as a more welcoming gateway to downtown for commuters, visitors, and residents of surrounding neighborhoods. This photo from the Asheville Times’ July 21, 1989 edition coincidentally ran along an article promoting the expansion of Asheville Mall to include Camelot Music, The Bombay Co., Claire’s Boutique, The Limited, Benetton, and Frank & Stein gourmet hot dogs.

- An additional phase expanded Glenn’s Creek Greenway into Weaver Park, but the original plan was for the greenway to run only between Merrimon Avenue and Broadway. Called W.T. Weaver Greenway and Broadway Greenway during planning stages, the names were changed to Glenn’s Creek Greenway and Reed Creek Greenway to reflect the City of Asheville’s preference for naming greenways for natural elements near their locations.

- With ample parking along W.T. Weaver Boulevard and inside Weaver Park, Glenn’s Creek Greenway is popular as both a way to travel and an out-and-back recreational loop for Ashevillians.

- Building Reed Creek Greenway was a joint effort and community members pitched in with donations of money and volunteer time.

- Reed Creek Greenway includes educational stations, public art, and biofilter areas. The distinctive stone bollards at cross streets resulted from community input and fundraising as a way to integrate the greenway into the Montford neighborhood.