This entry is part of Park Views, a weekly Asheville Parks & Recreation series that explores the history of the city’s public parks and community centers – and the mountain spirit that helped make them the unique spaces they are today. Read more from the series and follow APR on Facebook and Instagram for additional photos, upcoming events, and opportunities.

Asheville’s public park system includes regional destinations, town square-style community spaces, sports complexes, river access parks, playgrounds, community centers, and specialized facilities, but neighborhood parks sprinkled throughout the city showcase the diverse personalities of the people who bring to life this little corner of the world. At just under an acre, Owens-Bell Park proves even small spaces can reflect the big community spirit of those who live nearby.

The Railroad and the River

When the railroad came to Asheville in the 1880s, factories began appearing along tracks by the river. At the time, the area was referred to as West End because it was the westernmost developed part of the growing city. As houses for railroad and factory workers were built, neighborhoods that now make up West End Clingman Avenue Neighborhood (WECAN) came to life. Originally called Depot Street, Clingman Avenue became a bustling thoroughfare served by a trolley route taking people from the railroad depot to Aston Park and Pack Square.

When the railroad came to Asheville in the 1880s, factories began appearing along tracks by the river. At the time, the area was referred to as West End because it was the westernmost developed part of the growing city. As houses for railroad and factory workers were built, neighborhoods that now make up West End Clingman Avenue Neighborhood (WECAN) came to life. Originally called Depot Street, Clingman Avenue became a bustling thoroughfare served by a trolley route taking people from the railroad depot to Aston Park and Pack Square.

By the 1920s, it had emerged as a middle-class neighborhood for Black residents living in Queen Anne and Bungalow style homes with several family-owned businesses including a grocery store, bakery, drug store, hospital, churches, and school on Hill Street. West End, Prospect Park, Clingman Avenue, and other districts remained prosperous through the 1940s until the Haywood Road Connector razed dozens of homes, creating dead end streets that once were connected, and the Smoky Park Bridge (now Capt. Jeffrey Bowen Bridge) cut through Chicken Hill, eliminating several houses and small businesses. The expansion of Hilliard Avenue, factory closures, and sell off of railroad properties stunted development and no new houses were built for 50 years.

Out of Fire

In the 1990s, many in Asheville began to recognize the important connection WECAN served between burgeoning downtown revitalization and riverfront redevelopment. Though West End and Clingman Avenue developed as physically and culturally separate neighborhoods, residents and business owners of both began working together on a plan for the area.

In the 1990s, many in Asheville began to recognize the important connection WECAN served between burgeoning downtown revitalization and riverfront redevelopment. Though West End and Clingman Avenue developed as physically and culturally separate neighborhoods, residents and business owners of both began working together on a plan for the area.

Before the plan was complete, a 1995 fire destroyed several businesses and art studios located in the former Asheville Cotton Mill and Earle-Chesterfield Mill. This event began a larger conversation about the historical significance of the neighborhood. Community cleanups, block parties, and resident-driven improvements began to provide unity, protect historic buildings, and guide development rules for new construction. In 2004, Clingman Avenue Historic District and Riverside Industrial Historic District were both listed on the National Register of Historic Places.

Urban Oasis

Mountain Housing Opportunities (MHO) was founded in 1988 as a nonprofit to address the lack of quality affordable housing in Asheville. With its proximity to public transportation and jobs in downtown, MHO viewed WECAN as an ideal location for a series of projects and renovations that added several residential units to the neighborhood in the early 21st century. During the development of Merritt Park and Prospect Terrace, the nonprofit worked with established residents and new arrivals to design a park that would be donated to Asheville Parks & Recreation (APR) as a place to connect with neighbors and experience nature.

Mountain Housing Opportunities (MHO) was founded in 1988 as a nonprofit to address the lack of quality affordable housing in Asheville. With its proximity to public transportation and jobs in downtown, MHO viewed WECAN as an ideal location for a series of projects and renovations that added several residential units to the neighborhood in the early 21st century. During the development of Merritt Park and Prospect Terrace, the nonprofit worked with established residents and new arrivals to design a park that would be donated to Asheville Parks & Recreation (APR) as a place to connect with neighbors and experience nature.

Hundreds of volunteer hours would transform a ravine overgrown with kudzu, dead or dying trees, and non-native plants into a retreat with artistic benches, trees to provide shade, and a cultural garden with heritage plants from those who live in WECAN. Tight fitting boulders, shrubs, and granite curbstones from within the neighborhood were used to form a restored wetland ecosystem to manage runoff, reduce pollution, and enhance water quality. An industrial metal sign was installed to emphasize the connection to factories that once peppered the nearby river bank.

John H. Owens and Joseph D. Bell

As the unnamed park neared completion, utilizing the name of an individual who significantly contributed to the neighborhood was mentioned as a way to highlight WECAN’s past. The decision was made to honor two very distinguished gentlemen who lived in the neighborhood years prior.

As the unnamed park neared completion, utilizing the name of an individual who significantly contributed to the neighborhood was mentioned as a way to highlight WECAN’s past. The decision was made to honor two very distinguished gentlemen who lived in the neighborhood years prior.

John H. Owens moved into a house on Clingman Avenue in 1920 and owned a grocery store next door that he had opened the year before. With Owens Grocery Store on the north end and a barbershop on the other, the building acted as a community social space. It was located catercorner from the present-day park and is listed as the only surviving building that housed a business in Clingman Avenue Historic District, though it is now a residence.

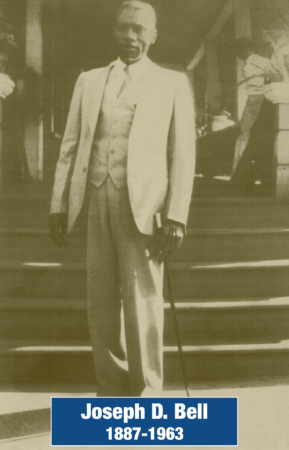

Remembered fondly as a colorful character, Joseph D. Bell was a war veteran active in the local American Legion post. As a retiree, he would often talk to young people in the neighborhood, emphasizing the need to stay in school and pursue careers. Many of these children went on to attend college and become professionals such as doctors, lawyers, and business owners.

Working Together

Owens-Bell Park was dedicated on September 4, 2006 and donated to the City of Asheville the following month. Even though it is a public park, it thrives off its connection to WECAN as the neighborhood association schedules regular garden and trail workdays and partners with APR on special projects. Visitors will find a small pavilion, benches, short paved loop, bridge and mulched trail, gardens, and large photos of the men for whom the park is named.

Do you have photos or stories to share about Owens-Bell Park? Please send them to cbubenik@ashevillenc.gov so APR can be inspired by the past as we plan our future.

Photo and Image Credits

- Photos of Owens (left) and Bell can be seen from the sidewalk along Clingman Avenue and the paved path in the park.

- French Broad River creates a natural corridor through the area, resulting in early Cherokee trails that became stagecoach routes and eventually railroad tracks. The arrival of rail service in 1880 transformed Asheville from a livestock town into a resort destination and center of commerce and healthcare for the region. Proximity to a water source and the availability of level building sites lured the city’s early industry to the river area. Southern Railway’s passenger and freight depot stimulated development of the area as Asheville’s primary industrial district. Courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

- The river district was both industrial and commercial, bustling with numerous manufacturing plants, textile mills, coal and lumber yards, wholesale businesses, and warehouses, along with various retail establishments and scattered dwellings. Many of the structures, including American Feed Milling Building (c. 1915), exist today as art studios, restaurants, offices, and retail businesses in the River Arts District. Original work by Upstateherd – own work, CC BY-SA 4.0, license.

- George Inge IV designed a funky, industrial sign to celebrate the artistic spirit of the park and the neighborhood’s historic connection to riverfront industry and modern reputation as a creative district full of artists. Granite curbstones from Jefferson Drive, Park Avenue North, and other neighborhood streets have been repurposed to line garden plots and flower beds.

- Owens opened a grocery store in 1919. He moved into the house next door in 1920 and lived there until he passed away at the age of 70.

- Bell was known for emphasizing education and personal responsibility among the neighborhood’s young people.

- The park’s dedication featured music, a centarian’s review of Asheville from Mr. Levie Wilson, and ribbon cutting attended by Owens’ and Bell’s descendants. Courtesy of WECAN.