This entry is part of Park Views, a Asheville Parks & Recreation series that explores the history of the city’s public parks and community centers – and the mountain spirit that helped make them the unique spaces they are today. Read more from the series and follow APR on Facebook and Instagram for additional photos, upcoming events, and opportunities.

Few public spaces as small as Triangle Park can take visitors on such a rich journey into Asheville history. However, the stunning murals that trace a timeline of local Black life are not the only reason this patch of land is an important community asset. Located within the city’s historic Black business district, Just Folks and other organizations host regular live music, celebrations, and fellowship events that keep Triangle Park active and inviting to all.

Isaac and Delia Dickson

Now generally defined as a 22-acre swath along Eagle and Market streets, The Block historically reached into areas as far north as College Street and as far south as today’s intersection of Biltmore Avenue and South Charlotte Street. Once the commercial center and entertainment hub for the city’s Black community, the district was connected to the East End/Valley Street and Southside neighborhoods until urban renewal in the 1970s forced the relocation of many families and businesses.

Now generally defined as a 22-acre swath along Eagle and Market streets, The Block historically reached into areas as far north as College Street and as far south as today’s intersection of Biltmore Avenue and South Charlotte Street. Once the commercial center and entertainment hub for the city’s Black community, the district was connected to the East End/Valley Street and Southside neighborhoods until urban renewal in the 1970s forced the relocation of many families and businesses.

The Block area was originally the quarters where the Patton family housed people they enslaved. Following emancipation, former slave Isaac Dickson purchased some of the Patton land near what is now Triangle Park for $275 in 1876. He rented houses on the property to freedmen and the larger area became known as Dicksontown, and then later East End. By 1890, his family was living at 139 Valley Street (now the site of the City of Asheville Public Works building). Along with his wife Delia, he ran a general store, coal yard, and taxi service next door. At a time when Jim Crow laws progressively undermined newly won rights, Dickson not only prospered but invested in many organizations that made Asheville a more vibrant community.

On August 31, 1890, along with Dr. Edward S. Stephens, Dickson hosted the first public meeting to organize the Young Men’s Institute, which would promote social and economic opportunities for Black residents. The center was completed in 1893, paid for by the Black community through a $10,000 loan secured from George Vanderbilt. Over the years, Dickson made many contributions to the YMI and The Block as treasurer of Venus Lodge No. 62, the first Masonic lodge for Asheville’s Black men.

Dickson also played a critical role in creating Asheville’s public school system. At the time, wealthy residents sent their children to private schools and opposed paying taxes to support public education. Former congressman Richmond Pearson (for whom Richmond Hill Park is named) actively campaigned for Black business owners and families to support public education proposals, promising a Black representative on the school board and no sharp rise in taxes. The Black community’s support proved crucial, as the proposal passed by just four votes in 1887. Pearson kept his promise and City Council appointed Dickson as the first Black member of the public school board.

Dickson also played a critical role in creating Asheville’s public school system. At the time, wealthy residents sent their children to private schools and opposed paying taxes to support public education. Former congressman Richmond Pearson (for whom Richmond Hill Park is named) actively campaigned for Black business owners and families to support public education proposals, promising a Black representative on the school board and no sharp rise in taxes. The Black community’s support proved crucial, as the proposal passed by just four votes in 1887. Pearson kept his promise and City Council appointed Dickson as the first Black member of the public school board.

The school board renovated a structure on Beaumont Street for the Black school and leased a former military academy for the white school. Both opened in January 1888 — the school for Black students a week before the white one. However, Beaumont Street School could hold only 300 students, severely lacking space for several hundred others who showed up on the first day. In 1891, city voters approved a bond referendum to build more schools including a Black school on Catholic Hill, completed the following year. After that three-story brick building burned in 1917, Stephens-Lee High School opened on its location in 1923.

Music, Church, and Community

From the late-19th century through the 1960s, Black residents of all social classes came to what The Block, actually a several-block area generally defined by Eagle Street, Biltmore Avenue, Hilliard Avenue, and Valley Street. Billiard rooms and music halls operated alongside doctors’ offices, drugstores, beauty and barber shops, cafes, candy shops, cultural and community centers, churches, jewelry stores, photo shops, hotels, cabstands, and cleaners. Some say The Block is so called because you could find anything you wanted within blocks of the YMI.

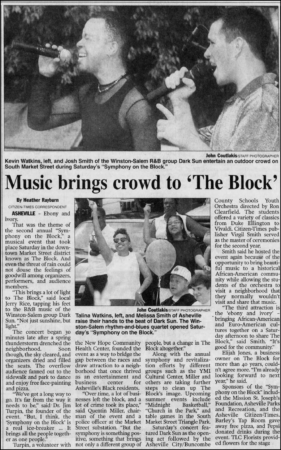

Top musical acts including Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong touring the South would play clubs and warehouses in The Block. Local bands, singers, and Piccolo jukeboxes also filled music halls like the Ritz and Club Del Cardo with sounds of the neighborhood into the morning hours when diners and cafes came to life.

Top musical acts including Duke Ellington and Louis Armstrong touring the South would play clubs and warehouses in The Block. Local bands, singers, and Piccolo jukeboxes also filled music halls like the Ritz and Club Del Cardo with sounds of the neighborhood into the morning hours when diners and cafes came to life.

Asheville Parks & Recreation’s (APR) programs for the Black community prior to integration were largely operated out of a two-story community center on Valley Street near Triangle Park. Activities included games, sports, dramatics, and arts and education classes in the building that also housed reading rooms, meeting places, a nursery school, and veterans’ sleeping quarters. The center’s annual report lists programming for five parks including one on Eagle Street. The YMI also housed the city’s library for its Black population nearby.

The architecture of The Block was heavily influenced by James Vester Miller, a master brick mason responsible for many important commercial and government buildings, churches, and private residences for both Asheville’s Black and white communities. Like Dickson, he was the son of an enslaved mother and a slavemaster father. Some of the remarkable buildings featuring his work that remain in The Block today include the YMI, J.A. Wilson Building, Mt. Zion Missionary Baptist Church, and Asheville Municipal Building. A marker on the Urban Trail (unveiled during 1996’s Goombay festival) and bronze plaque on the Municipal Building highlight his role in building Asheville.

Bringing a Park Back to The Block

The combination of urban renewal projects and integration in the 1960s and 1970s disrupted almost all of the physical and institutional foundations of Black life in Asheville. The Block’s historic connection to East End was severed when the neighborhood’s main artery, Valley Street, was widened and renamed South Charlotte Street after the sister-in-law of slave owner James W. Patton. Several homes, businesses, institutions, and even whole streets were decimated during the redevelopment project.

The combination of urban renewal projects and integration in the 1960s and 1970s disrupted almost all of the physical and institutional foundations of Black life in Asheville. The Block’s historic connection to East End was severed when the neighborhood’s main artery, Valley Street, was widened and renamed South Charlotte Street after the sister-in-law of slave owner James W. Patton. Several homes, businesses, institutions, and even whole streets were decimated during the redevelopment project.

The Block transformed from a vibrant, lively district to one filled with a few restaurants, retail shops, and entertainment venues; it was no longer the main space for community congregation. What had once been a town square for community-as-family celebrations became run down. In the 1980s, the idea to transform a small triangle situated between South Market and Sycamore streets into a park gained traction.

When it opened as a city park with trees, landscaped beds, and benches, it became a place to connect with neighbors and host birthday parties and reunions. Partnerships between APR and community groups like Spirit on the Block, the YMI, New Hope, South Pack Square Community Center, Just Folks, and Eagle/Market Street Redevelopment Corporation brought more visibility to the space through concerts, festivals, and wellness programs. It was often the location of a performance stage during Goombay, outdoor movies under the stars, and Music on the Block during the 1990s and 2000s. During that time, Asheville Police Department held Midnight Madness basketball tournaments for local kids using the Public Works parking lots as courts and Triangle Park for refreshments and a resting area.

Gateway to History

As the park’s visibility grew, support grew among the generation that came of age during The Block’s prime to install public art celebrating the neighborhood’s history. After a decade of fundraising (including a grant from APR), Just Folks unveiled the first seven sections of a mural memorializing local milestones made possible by Black community leaders including the establishment of Dicksontown, the region’s railroad system built mostly by Black men, the YMI, Catholic Hill School, and Stephens-Lee High School. Subsequent panels were added to showcase life in East End and The Block before urban renewal and celebrate Black excellence in the arts, sports, and civic leadership.

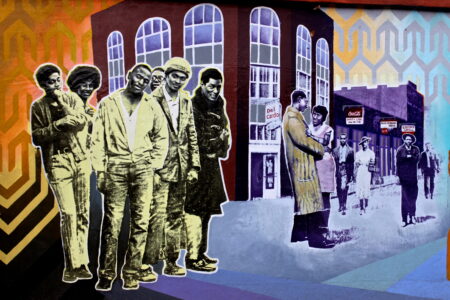

Just Folks collaborated with Asheville Design Center and lead artist Molly Musk to paint the mural incorporating personal memories, historical archives, and photographs including some from the collection of photographer Andrea Clark, the granddaughter of James Vester Miller whose many images of life in East End provide a valuable portrait of the community. Using a unique transfer process, the larger-than-life art pieces transport park visitors through decades of local history. It is part of the Appalachian Mural Trail.

Just Folks collaborated with Asheville Design Center and lead artist Molly Musk to paint the mural incorporating personal memories, historical archives, and photographs including some from the collection of photographer Andrea Clark, the granddaughter of James Vester Miller whose many images of life in East End provide a valuable portrait of the community. Using a unique transfer process, the larger-than-life art pieces transport park visitors through decades of local history. It is part of the Appalachian Mural Trail.

In 2021, APR renovated the park with resodded grass areas and a new irrigation system, redesigned landscaping for better visibility and shade, and replacement of benches, picnic tables, and other park furniture. That same year, Buncombe County Remembrance Project and Equal Justice Initiative installed a historical marker to document the lynching of Bob Brackett by at least 1,000 white people on August 11, 1897 in Buncombe County.

As The Block welcomes new neighbors and new businesses, Triangle Park is firmly planted in celebrating the legacy and preserving the culture of Black life in Asheville.

Do you have photos or stories to share about Triangle Park? Please send them to cbubenik@ashevillenc.gov so APR can be inspired by the past as we plan our future.

Photo and Image Credits

- Known as Dicksontown, Velvet Street, Valley Street, and East End, the area east of today’s Biltmore Avenue and south of College Street to Beaucatcher Mountain flourished through the first half of the 20th century, but was fragmented and displaced by 1980. However, photographs of a strong and connected community remain. Personal photographs and oral histories were used in the creation of Triangle Park’s mural. To the right of this panel is a quote from Langston Hughes. On the left, an inscription incorporating neighborhood streets, some that no longer exist: “These are the days of riches, of Velvet & Pine, Lincoln, Hazard, and Valley – the vine. Streets are homelands and pockets are deeper ‘cause nobody thirsts when you’re each other’s keepers.”

- The arrival of rail service to Asheville transformed the community from a livestock town to the center of commerce for the region, but much of the area that would become The Block had yet to be developed in 1891. Ruger & Stoner & Burleigh Litho. (1891) bird’s-eye view of the city of Asheville, North Carolina. [Madison, Wis] [Map] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/75694894.

- Following the emancipation of enslaved people in the United States, Isaac Dickson moved to Asheville with his wife Cordelia Reed after living in Morganton for a short time. As an active and upstanding community leader, he was instrumental in shaping the city from his arrival until his death in 1919. Isaac Dickson Elementary School on Hill Street is named for him, recognizing his role in establishing the public education system.

- One of Triangle Park’s mural panels showcases businesses and fashions through decades of life in The Block. Ebony Grill, Blue Ribbon Grill, Darity Cabs, and Club Del Cardo are only four of the well-loved spots remembered by those who grew up during the district’s heyday. The Del Cardo Building now houses LEAF Global, an interactive museum and arts center. Courtesy of Denise Carbonell, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons.

- Music on The Block (also known as Symphony on The Block, Health on The Block, and other names) brought music to Triangle Park for many seasons. Now luxury condos, the lot across the street from the park was an auto repair shop and parking lot that allowed overflow crowds to dance and elders to enjoy the music from the comfort of lawn chairs. Courtesy of Asheville Citizen Times.

- Nearly 100 volunteers helped paint Triangle Park’s mural in 2012 and 2013. Based on the history, photographs, and stories of the people of East End, artist Molly Must composed the design with contributions by artists Ernie Mapp, Twila Jefferson, Ian Wilkinson, Harper Leich, and Liana Murray. The Just Folks Mural Team included Ceretha Griffin, Curtis James, Linda Jackson, Julia McDowell, Francena Griffith, and Timothy Burdine. Mosaics were completed by Donald Norris with help from Mr. Pedro, Danny Suber, and Alex Irvine. Courtesy of Molly Musk.