This entry is part of Park Views, an Asheville Parks & Recreation series that explores the history of the city’s public parks and community centers – and the mountain spirit that helped make them the unique spaces they are today. Read more from the series.

Named for the man who played a large role in modernizing Asheville’s image with his streetcar network and hydraulic energy production, Weaver Park represents a turning point for the city’s parks. With a few exceptions including Walton Street Park, Asheville had yet to embrace parks as multi-use spaces featuring varied amenities like ballfields, tennis courts, basketball courts, playgrounds, and picnic shelters in one location to bring recreation directly into neighborhoods.

Coming Down the Lines

William Trotter Weaver was born in the Reems Creek valley near Weaverville in 1858. After his father was killed leading a Confederate regiment, his family  moved to South Carolina before returning to the area where he attended school. Weaverville is named in honor of the Rev. Montraville Weaver, his great uncle.

moved to South Carolina before returning to the area where he attended school. Weaverville is named in honor of the Rev. Montraville Weaver, his great uncle.

After working as a business clerk and in a cotton mill, raising livestock, and operating a general store on Pack Square, he became Asheville’s postmaster in 1885 and president of a bank a few years later. In 1887, he married Annie Johnston, whose father donated land for a post office that eventually became Pritchard Park.

Edwin Carrier, a hotelier and entrepreneur from whom Carrier Park gets its name, opened the area’s first hydroelectric plant in 1890 and soon after built two generators on Hominy Creek to provide power for the city’s expanding streetcar network and street lights. When Weaver’s Asheville Electric Company acquired a street rail system in 1897, these facilities became part of the new company to power its trolleys.

Weaver also recognized advantages a larger plant on the French Broad River could bring, incorporating W.T. Power Company and opening a power plant near Big Craggy in 1904. Shortly after, the new hydroelectric operation supplied all of Asheville Electric Power  Company’s needs for four consolidated street railway lines in the city, as well as serving residential and commercial customers. W. T. Weaver Power Company opened additional plants along the French Broad at Ivy and Elk Mountain.

Company’s needs for four consolidated street railway lines in the city, as well as serving residential and commercial customers. W. T. Weaver Power Company opened additional plants along the French Broad at Ivy and Elk Mountain.

During the Flood of 1916, several power plants along the river were inundated. After spending long days alongside crews repairing damage, Weaver became seriously ill and passed away that November. He is buried at Riverside Cemetery.

After Weaver’s death, the power company continued until 1923 when it became part of Electric Bond and Share Company. Later consolidated with Asheville Power and Light Company, it was acquired by Carolina Power and Light Company, remaining as part of Duke Energy today.

Planning

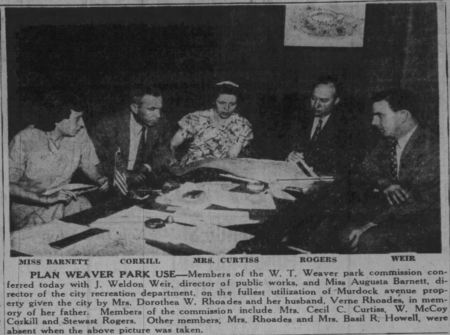

In 1947, W.T. and Annie Weaver’s daughter approached the City of Asheville to create a public park through land donation named for her father. Already colloquially known as Weaver’s Park, the wooded area between Murdock and Merrimon avenues was popular for picnicking and playing. While parks and recreation services were part of the Public Works department at the time, Asheville Parks & Recreation (APR)’s first director Augusta Barnett was involved in planning the new park in her role as recreation supervisor.

In 1947, W.T. and Annie Weaver’s daughter approached the City of Asheville to create a public park through land donation named for her father. Already colloquially known as Weaver’s Park, the wooded area between Murdock and Merrimon avenues was popular for picnicking and playing. While parks and recreation services were part of the Public Works department at the time, Asheville Parks & Recreation (APR)’s first director Augusta Barnett was involved in planning the new park in her role as recreation supervisor.

Dorthea Weaver Rhoades shared her parents’ commitment to community and conservation. After college, she returned to Asheville to serve with the American Red Cross and YWCA of Asheville, becoming the youngest YWCA president in the nation in 1925. The next year, she married Verne Rhoades Sr., a scientific forester who played an important role in creation of Pisgah National Forest and Great Smoky Mountains National Park.

Rhoades and a public commission began planning the park named for her father while crews started clearing underbrush and straightening a creek known as Weaver’s Bottom that ran through the property to Woolsey Dip. Initial plans included restrooms, a picnic shelter, softball and football fields, tennis courts, horseshoe pitches, shuffleboard layouts, and a playground. To accommodate the park, Murdock Avenue doubled in size with wider medians and plantings to provide a parkway feel.

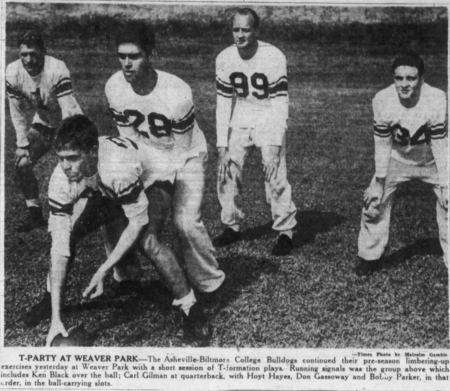

By 1948, area high schools and the Asheville-Biltmore College Bulldogs practiced football and held scrimmages in the park. The college relocated near the park in 1961 and the Rhoades family granted the city a right of way to build W.T. Weaver Boulevard to access the new campus. Asheville-Biltmore College adopted its current name of UNC Asheville in 1969. Dorthea was active in development of nearby Botanical Gardens at Asheville and her sons later donated several acres to the university that are now part of Glenn’s Creek Greenway.

By 1948, area high schools and the Asheville-Biltmore College Bulldogs practiced football and held scrimmages in the park. The college relocated near the park in 1961 and the Rhoades family granted the city a right of way to build W.T. Weaver Boulevard to access the new campus. Asheville-Biltmore College adopted its current name of UNC Asheville in 1969. Dorthea was active in development of nearby Botanical Gardens at Asheville and her sons later donated several acres to the university that are now part of Glenn’s Creek Greenway.

In addition to football, Weaver Park’s size made it a popular spot for baseball, volleyball, and archery. However, the northern section of the park saw frequent flooding as a result of altering Weaver’s Bottom, referenced as both Glenn’s Creek and Reed Creek (with alternate spellings for both) on property maps. When Beaver Lake’s pool closed in 1952, the park’s flood zone was floated as a potential site for a public pool.

Expansion

Adding amenities like a pool proved challenging for a number of reasons, primarily funding and location. At the time, the City of Asheville operated 13 major parks and three swimming pools on a budget of just $100,000. Neighbors along Murdock Avenue also objected to features that might attract larger crowds, annoyed by cars blocking road access during ball games.

The park’s neighbors for years successfully blocked installation of field lights at the park’s diamond with one resident telling City Council that night games would only attract more little boys who should be studying instead of playing baseball and “impressing each other by uttering the vilest phrases.” In 1956, lights were installed on a trial basis with promises to remove them if neighbors still held objections. Ironically, the lights were removed from the park named for the person largely responsible for building the city’s electrical grid after one summer and installed at Biltmore High School.

The park’s neighbors for years successfully blocked installation of field lights at the park’s diamond with one resident telling City Council that night games would only attract more little boys who should be studying instead of playing baseball and “impressing each other by uttering the vilest phrases.” In 1956, lights were installed on a trial basis with promises to remove them if neighbors still held objections. Ironically, the lights were removed from the park named for the person largely responsible for building the city’s electrical grid after one summer and installed at Biltmore High School.

As neighborhoods around Merrimon Avenue grew, many argued another park was badly needed. APR proposed building a playground near Ira B. Jones School, but residents near the school highly opposed the idea. Eventually, a ballfield with public access was added near the school.

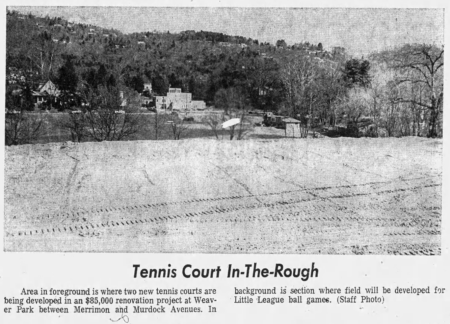

A 1966 assessment of Asheville’s park system recommended acquiring the additional land to build tennis courts, so the Rhoades family donated an additional 2.25 acres to expand Weaver Park. Part of the original park vision, construction began, but loss of local sales tax revenue halted progress until APR secured $85,000 in federal funding. The lighted courts’ location became level with Merrimon Avenue using fill dirt. New parking lots flanked the east and west ends of the park, redirecting flow of runoff to the park stream making it wider and deeper.

A 1966 assessment of Asheville’s park system recommended acquiring the additional land to build tennis courts, so the Rhoades family donated an additional 2.25 acres to expand Weaver Park. Part of the original park vision, construction began, but loss of local sales tax revenue halted progress until APR secured $85,000 in federal funding. The lighted courts’ location became level with Merrimon Avenue using fill dirt. New parking lots flanked the east and west ends of the park, redirecting flow of runoff to the park stream making it wider and deeper.

The funding also brought field lighting back to the diamond. In the process, the backstop was relocated to orient the ballfield away from the center of the park and bleachers for up to 500 spectators were added. Crews razed a caretaker’s house and replaced it with a new restroom and storage building. An expanded playground, new picnic shelter, renovated basketball court, and arched bridges connecting the “new” and “old” sections across the creek completed Weaver’s new layout by 1975.

Restoration

Through the 1980s, Weaver remained one of the city’s most popular parks and its most-used playground, which was completely replaced in 1996 with accessible features. The picnic shelter was even used as a voting location in 2001 when Beth Israel Synagogue, located across the street and the usual precinct voting location, was unavailable due to Sukkot celebrations.

Through the 1980s, Weaver remained one of the city’s most popular parks and its most-used playground, which was completely replaced in 1996 with accessible features. The picnic shelter was even used as a voting location in 2001 when Beth Israel Synagogue, located across the street and the usual precinct voting location, was unavailable due to Sukkot celebrations.

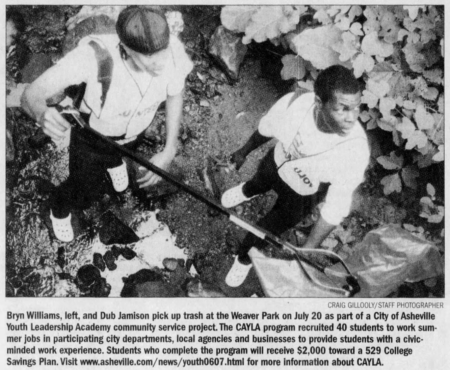

Renewed interest in environmental restoration led to a three-year study of the park stream that recorded high phosphorus values, nutrients, and heavy metals commonly associated with urban runoff, restricting potential for development of crayfish, snails, worms, and other macroinvertebrates. When the North Carolina Department of Transportation’s widening of US 74 impacted Gashes Creek, the agency needed a nearby area for wetland mitigation to offset the project. With the report in hand, APR proposed repairing Weaver Park’s riparian buffer with grass, trees, and shrubs and removing invasive species.

As part of the restoration project, the Rhoades Trust donated an additional half acre of land to allow Glenn’s Creek Greenway’s path to meander through Weaver Park, cross Merrimon Avenue, and along Weaver Boulevard until it connects with Reed Creek Greenway at the botanical gardens and Broadway.

Plans for Weaver Park’s next chapter are underway with resurfaced basketball and dual-lined tennis/pickleball courts, repaved parking lots, improved lighting, an accessible bridge over the creek, and a new playground on the way.

Plans for Weaver Park’s next chapter are underway with resurfaced basketball and dual-lined tennis/pickleball courts, repaved parking lots, improved lighting, an accessible bridge over the creek, and a new playground on the way.

Do you have photos or stories to share about Weaver Park? Please send them to cbubenik@ashevillenc.gov so APR can be inspired by the past as we plan our future. Sign up for APR’s monthly newsletter and follow APR on Facebook and Instagram for additional photos, upcoming events, and opportunities.

Photo and Image Credits

- A new bridge installed at Weaver Park connects its western portion featuring dual-lined tennis/pickleball courts with the eastern portion featuring a ballfield, basketball courts, picnic shelter, playgrounds, and restrooms as part of Glenn’s Creek Greenway. It’s at least the fourth bridge installed since the eastern portion near Merrimon Avenue was developed in the 1970s.

- This stereograph of Pack Square was taken looking north from Western Hotel (c. 1883-1888) shows W.T. Weaver’s Dry Goods Store on the right. Other buildings include Buck Hotel, Graham & Redwood, J.J. Hill & Co. Furniture Dealers (with a chair on the roof), and I. Levy’s Dry Goods Store. Courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

- W.T. Weaver Power Company built a hydroelectric facility and Craggy Dam Reservoir in 1904 to supply power to Asheville Electric Company’s street railways. In 1926, Carolina Power and Light Company bought the dam and operated it until 1963. Soon after, Metropolitan Sewerage District (MSD) purchased the facility. During early phases of construction or MSD’s wastewater reclamation facility in the 1960s, Riverside Drive relocated westward to expand the plant’s footprint and approximately two-thirds of the hydroelectric facility’s original flume was filled in and abandoned. In 1984, MSD reconstructed portions of the flume and began generating power to offset its electrical demand. This print is made from an original glass negative by John Caldwell estimated to have been taken in 1905. Courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

- Though planners originally envisioned Asheville as a network of parks, plazas, and parkways, the city’s massive debt following local bank failures in 1930 led to a largely stagnant park system. Weaver Park represented a new era of community planning in which residents fully participated.

- Asheville-Biltmore College’s football team practiced in the park and played games at Memorial Stadium. It relocated to an area near Weaver Park, adopted the UNC Asheville name, and connects to the park today via Glenn’s Creek Greenway.

- A large stone designating the park was placed near the ballfield in 1949. During the park’s 1975 reconfiguration, it moved to a new parking area created off Murdock Avenue.

- Asheville’s reputation as a tennis destination dates to the 19th century, but the 1970s saw access greatly expanded. Perhaps fueled by national interest in Billie Jean King and Bobby Riggs’ Battle of the Sexes match, new courts opened at Aston Park Tennis Center and modern surfaces replaced asphalt and pavement at other public parks throughout the city.

- Community members including these City of Asheville Youth Leadership Academy (CAYLA) interns have helped reverse decades of human interference near the stream that runs through Weaver Park.

- Similar to its 1970s facelift, Weaver Park welcomes visitors with fresh amenities and modern accessibility.