This entry is part of Park Views, an Asheville Parks & Recreation series that explores the history of the city’s public parks and community centers – and the mountain spirit that helped make them the unique spaces they are today. Read more from the series and follow APR on Facebook and Instagram for additional photos, upcoming events, and opportunities.

The French Broad River is believed to be one of the oldest rivers in the world, an ancient water trail that has been an inheritance to plants, animals, and humans. What had been the site of recreation for thousands of years became a floating mess of sewage and pollution by the mid-20th century. An Asheville native’s book brought attention to the blighted waterway and inspired a social, environmental, and economic vision to protect the river flowing through the heart of Asheville. Wilma Dykeman Greenway is named for her.

Recreation on the River

The joining of the French Broad and Swannanoa rivers roughly marks the eastern boundary of Cherokee homelands in western North Carolina that included towns and villages, complete with defensive palisades, hunting grounds, and plazas for ball play along the riverbanks. Different sections of the river had their own names to reflect contrasting moods and natural elements.

The joining of the French Broad and Swannanoa rivers roughly marks the eastern boundary of Cherokee homelands in western North Carolina that included towns and villages, complete with defensive palisades, hunting grounds, and plazas for ball play along the riverbanks. Different sections of the river had their own names to reflect contrasting moods and natural elements.

ᏙᎩᏯᏍᏗ (Togiyasdi, “the place where they race”) was the name given to the confluence of the two rivers in modern-day Asheville. Many of the trails the Cherokee established along waterways and through forests for travel, food gathering, recreation, and commerce eventually turned into stagecoach trails like the Buncombe Turnpike, then railroads, and eventually modern roads and greenways.

When white settlers first arrived in the Appalachians, they devised their own names for natural landmarks such as rivers and mountains. With headwaters near Rosman in Transylvania County, new mountaineers saw the French Broad flow north through Henderson, Buncombe, and Madison counties and west into Tennessee towards the Mississippi River and France’s colonized territory.

Factories began appearing along the river when the railroad arrived in the 1880s, transforming Asheville from a livestock town into the region’s economic center. For the next several decades, the riverfront district would operate as one of the area’s primary industrial areas due to its proximity to the railway. Electric streetcars connected the bustling riverfront with Pack Square, Aston Park, and other areas of the growing city.

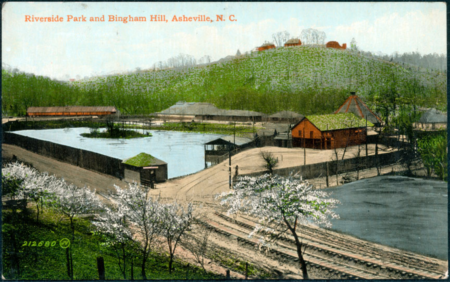

The riverfront was also home to some of the city’s earliest parks. Completed in 1892, Carrier’s Field (near today’s Carrier Park) hosted horse races, baseball games, bicycle races, and other sporting events for guests of Hotel Belmont. Asheville Electric Company opened Riverside Park in 1904, a popular spot on the river near Pearson Bridge with a horse track, lake, ballfield, casino, and amusement rides that operated until the Flood of 1916 destroyed it.

Who Killed the French Broad?

The severity of the Flood of 1916 brought development along Asheville’s riverfront to a halt. Proximity to the river played an important role in both the city’s formation and the growth of its urban core that favored the valley’s flat terrain for rail transportation. However, the community had already begun expanding farther from the river with the arrival of personal automobiles leading to new business and residential centers.

The severity of the Flood of 1916 brought development along Asheville’s riverfront to a halt. Proximity to the river played an important role in both the city’s formation and the growth of its urban core that favored the valley’s flat terrain for rail transportation. However, the community had already begun expanding farther from the river with the arrival of personal automobiles leading to new business and residential centers.

By the 1950s, Asheville’s rapid population growth turned the French Broad into an open cesspool in the form of floating sewage, garbage disposal, industrial and chemical runoff, and landfill seepage. Residents and businesses left the riverfront behind to auto graveyards, junkyards, abandoned buildings, and rundown factories that straight-piped waste directly into the river. Pollution was so bad that it was considered a “dead river” and several native fish and aquatic species became extinct.

Wilma Dykeman’s first book, The French Broad, was released in 1955. The collection of stories depicting historical events connected to the river included chapters about the Civil War, formation of Tennessee Valley Authority (TVA), and biographies of colorful characters alongside those covering pollution and water contamination. Her publisher initially rejected a section that addressed river pollution as too controversial. She retitled the chapter “Who Killed the French Broad?” to make it sound like a murder mystery and it remained in the text.

Wilma Dykeman

The French Broad serves as an important link between the beginning of the U.S. environmental movement of the 1960s and the earlier conservation movement. By connecting clean air and water with economic development and human well-being, Dykeman stressed the importance of understanding history and using that knowledge to go forward, writing, “Dwellers of the French Broad country are learning an ancient lesson in all their resources: it is easy to destroy. Because the river belongs to everyone, it is the possession of no one. And as towns and villages grew, they dumped their trash. Filth is the price we pay for apathy.”

The French Broad serves as an important link between the beginning of the U.S. environmental movement of the 1960s and the earlier conservation movement. By connecting clean air and water with economic development and human well-being, Dykeman stressed the importance of understanding history and using that knowledge to go forward, writing, “Dwellers of the French Broad country are learning an ancient lesson in all their resources: it is easy to destroy. Because the river belongs to everyone, it is the possession of no one. And as towns and villages grew, they dumped their trash. Filth is the price we pay for apathy.”

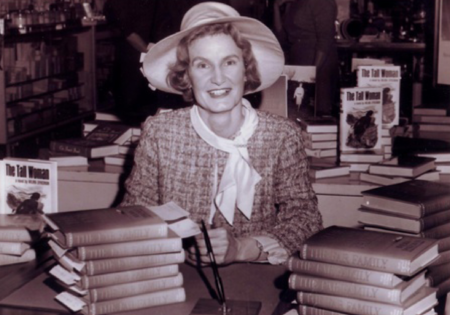

With a lifetime love of reading and writing inspired by her parents, Dykeman would write 18 books including three biographies and three historic novels, most focused on the mountains of western North Carolina and east Tennessee. Along with a commitment to environmental activism that was ahead of its time, she wrote Neither Black Nor White with her husband James Stokely, receiving the Hillman Prize for contributions to social justice for social good.

In addition to her progressive position on race relations, Dykeman felt that “the Appalachian  woman has had a rather difficult time being understood.” To dismantle the stereotype of mountain people being simpleminded and backwards, she wrote her first work of fiction, The Tall Woman. The heroine of the novel brings a community together to build a school for Appalachian children, highlighting Dykeman’s unyielding beliefs in the value of education.

woman has had a rather difficult time being understood.” To dismantle the stereotype of mountain people being simpleminded and backwards, she wrote her first work of fiction, The Tall Woman. The heroine of the novel brings a community together to build a school for Appalachian children, highlighting Dykeman’s unyielding beliefs in the value of education.

Raised in the Beaverdam area, Dykeman and Stokely’s family divided their time between Asheville and Newport, Tennessee. She taught courses in Appalachian literature and creative writing at University of Tennessee for 20 years and wrote a column for Knoxville News Sentinel from 1962 until 2000. In addition to her books, public speaking, and teaching, Dykeman wrote short stories and articles for periodicals including The New York Times Magazine and Harper’s.

Among her many honors were the Guggenheim Fellowship and the 1985 North Carolina Award for Literature. She also held the title of Tennessee State Historian from 1981 until her death in 2006.

Rescuing the French Broad

In 1961, TVA proposed building a series of 14 hydroelectric dams in the French Broad watershed that would have flooded more than 18,000 acres of mountain valleys including the Warren Wilson College farm. While the $100 million project had near universal acceptance among local government leaders, a grassroots group of “dam fighters” organized as the Upper French Broad Defense Association, waging a multiyear campaign against the massive project.

In 1961, TVA proposed building a series of 14 hydroelectric dams in the French Broad watershed that would have flooded more than 18,000 acres of mountain valleys including the Warren Wilson College farm. While the $100 million project had near universal acceptance among local government leaders, a grassroots group of “dam fighters” organized as the Upper French Broad Defense Association, waging a multiyear campaign against the massive project.

The group demanded that TVA hold public hearings, which lasted for three days in Asheville and were attended by hundreds of people who donned homemade yellow scarves in protest. TVA abandoned the plan; in the process, the community decided to embrace the river, setting the stage for a French Broad rebound.

In 1976, Land of Sky Regional Council obtained a small grant from TVA to begin a regional approach to long range planning for the French Broad River. Over the next decade, river cleanup efforts and the annual French Broad River Week festival led to the formation of RiverLink. Around the same time, artists and creators began moving into the Asheville riverfront’s vacant industrial buildings and transforming them into large and small studios.

Asheville’s Riverfront Plan was unveiled in 1989 and the beginning of the city’s greenway system became a reality when a paved loop opened in French Broad River Park in 1995.

Asheville City Council in 2004 unanimously approved The Wilma Dykeman RiverWay Master Plan, a detailed master plan for urban areas along the French Broad and Swannanoa rivers. It took Dykeman’s words as guidance: “Just as the river belongs to no one, it belongs to everyone – and everyone is held accountable for its health and its condition. Every city and town and every industry is responsible for cleaning up the pollution it creates.”

A RAD Greenway

The success of French Broad River Park led Asheville Parks & Recreation (APR) to develop Amboy Riverfront and Carrier parks on the west bank – and then French Broad River Greenway to connect them with Buncombe County’s Hominy Creek River Park. Organized studio strolls in the industrial riverfront district started in 1994, leading to an organizing committee which named itself River Arts District Artists. Today, the area on the east side of the river is well known as the River Arts District (RAD).

The success of French Broad River Park led Asheville Parks & Recreation (APR) to develop Amboy Riverfront and Carrier parks on the west bank – and then French Broad River Greenway to connect them with Buncombe County’s Hominy Creek River Park. Organized studio strolls in the industrial riverfront district started in 1994, leading to an organizing committee which named itself River Arts District Artists. Today, the area on the east side of the river is well known as the River Arts District (RAD).

A major piece of The Wilma Dykeman RiverWay Plan was realized in 2021 when a large transportation and design project in the RAD reconfigured unsafe road intersections for better traffic flow, established constructed wetlands as part of a stormwater management network, installed wide sidewalks for pedestrians, provided almost 200 new public parking spaces, added nine acres of new parkland, and installed several new pieces of public art. Serving as the main activator for all of these elements is a greenway on the east bank of the French Broad.

Asheville’s first official greenway plan recommended naming greenways after natural features like creeks and rivers. During planning and construction, the new path was called French Broad River East to differentiate it from French Broad River Greenway on the west side of the river. Following a public vote, WIlma Dykeman Greenway opened with a month of celebrations in 2021 that began on Earth Day and ended on May 20, its namesake’s birthday.

Asheville’s first official greenway plan recommended naming greenways after natural features like creeks and rivers. During planning and construction, the new path was called French Broad River East to differentiate it from French Broad River Greenway on the west side of the river. Following a public vote, WIlma Dykeman Greenway opened with a month of celebrations in 2021 that began on Earth Day and ended on May 20, its namesake’s birthday.

The greenway currently has trailheads at the Amboy Road-Lyman Street intersection and the Hill Street-Riverside Drive intersection. A planned mile of Wilma Dykeman Greenway will extend to the intersection of Broadway and Riverside Drive, connecting to a future greenway along the river in Woodfin.

The two-mile, accessible greenway’s path is dotted with benches, bike racks, and public art including a larger-than-life sprocket and 13 Bones pedestrian bridge. Wilma Dykeman Greenway is also the city’s first with lighting for nighttime use, first with a two-way protected bike lane, and first with a public boat ramp (in Craven Street Park). River access is also available along the greenway using steps at Jean Webb Park, a space named for another strong local voice of the river with an educational pollinator meadow maintained by Asheville GreenWorks.

Wilma Dykeman was a pioneer in helping people understand that environmental stewardship goes hand-in-hand with economic development, but she also stressed people have a limited amount of time on earth to make a difference. As community members continue to promote her vision of sustainable economic growth along Asheville’s waterways, they can also enjoy walking, biking, rolling, and other human-powered forms of exercising and commuting while enjoying decades of work to revive the French Broad.

Do you have photos or stories to share about Wilma Dykeman Greenway? Please send them to cbubenik@ashevillenc.gov so APR can be inspired by the past as we plan our future.

Photo and Image Credits

- Wilma Dykeman Greenway’s design features functional elements and public art that compliment the natural elements of the French Broad River. Courtesy of Barnhill Contracting Company.

- Riverside Park was one of the most popular of Asheville’s early parks. Electric street cars – also known as trolleys – operated by Asheville Electric Company brought community members to a park that featured a casino, merry-go-round, skating rink, dance hall, horse track, ballfield, two small lakes, and a “zoo” with groundhogs, raccoons, and a bear. Special events included fireworks displays, summer concerts, and motion picture exhibitions. Newspaper articles describe a sometimes-rowdy crowd. Fire damaged some of the buildings shortly before the Flood of 1916 destroyed the park and it was abandoned. Courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

- Though floods had hit Asheville before, the Flood of 1916 broke every record in the book. The death and destruction it caused in western North Carolina defined flooding for an entire generation. Waters rose higher than treetops, consuming entire homes and lower levels of factories. Though Asheville’s industrial district would continue to operate as such for several years, the flood marked the beginning of a low point for the area. Courtesy of Buncombe County Special Collections, Pack Memorial Public Library, Asheville, North Carolina.

- Dykeman wrote 15 nonfiction books and three novels including The Tall Woman. Of her decision to write her first novel, she remarked, “What has usually stirred societies, historically, to action? We had any number of reports about slavery, but it was Uncle Tom’s Cabin that lit the fuse. A novel, there, really galvanized the whole action. What is it that we have from societies today that we remember, that we know about societies of the past, their conflicts? It’s the literature. It is absolutely essential that we each respect each other.” A common theme of her work is elevating the people of Appalachia, showing how their personal stories helped change America. Courtesy of University of North Carolina Asheville Special Collections.

- Dykeman and Alex Haley, author of Roots and The Autobiography of Malcolm X, both served on the Berea College Board of Trustees. She was the first woman trustee and taught courses through the Berea College Department of English and Theatre. Courtesy of University of North Carolina Asheville Special Collections.

- As the community started to see results from grassroots activism, organizations including RiverLink and APR leveraged that enthusiasm to win grants to expand river access and parks in the watershed. In 1997, locals campaigned for federal funds attached to the French Broad being named one of 10 American Heritage Rivers, as seen in this Asheville Citizen-Times article. Dykeman supported the move, saying, “The French Broad is not the widest or the longest or the deepest of rivers, but there are few that can equal its diversity. We are creating a heritage, and that’s what this initiative can do. Diversity is our heritage, but unity is our strength.”

- Wilma Dykeman Greenway has a number of features including swinging benches inspired by the riverfront’s industrial history. Courtesy of Barnhill Contracting Company.

- Public art makes the greenway feel like a linear museum set in nature. Courtesy of Barnhill Contracting Company.